An Interview with the Writer of SILAS THE UNINVITED

An Interview with Derek J. Snow, writer of SILAS THE UNINVITED by Theatre 200 practicum student Jack Troiano.

I think I'll start this interview with a bit of a softball: what's your favorite color?

Red.

Nice. Any reason?

No, I don't think so. I was an art major as a kid; my mother used to take me to a place called the Art Academy. And they noticed as early as the fourth grade that everything I painted and colored was red. So I'm like, "Yep, definitely my favorite color." So it's been that way since I was little. I don't know why.

Who are some of your theatrical and artistic inspirations?

I have to start with August Wilson. I was in school, in college at the time, and I was classically trained as an actor. I had done a lot of Moliere and a lot of Chekhov and a lot of Shakespeare, but he was the first Black playwright that actually opened my eyes artistically to a different way of writing, a different style. It felt more in line with my own upbringing. So I connected immediately to that. Also, Cheryl West, another playwright in that same vein who wrote mostly early-era plays about HIV when the AIDS crisis was a big deal in the '90s. And definitely, Suzan Lori Parks, who wrote Top Dog Underdog and In the Blood and a few other ones that I really love. So those are people, even as an actor, I admired – before I even started writing. I love the classics. I loved being raised in that classical atmosphere as an actor. I've been acting for 35-plus years, so I really enjoy that part of theatre too. But now, I'm starting to love the creation of my own stories and characters as well.  With this background in acting, what specifically motivated you to create SILAS THE UNINVITED?

With this background in acting, what specifically motivated you to create SILAS THE UNINVITED?

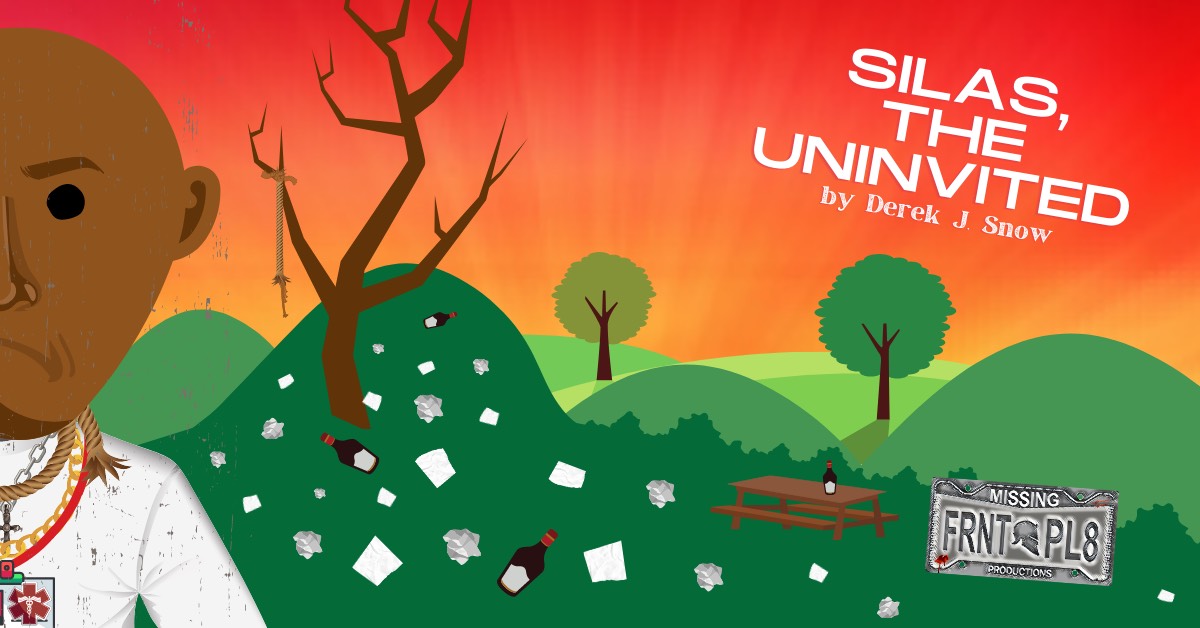

Sure, primarily the killing of a good friend of mine; one of my best childhood friends was killed by a police officer in Cincinnati in 2015. He was pulled over for a missing front license plate and ended up losing his life, and I named my company Missing Front Plate Productions for that reason. But more specifically to SILAS, I was tired of the politicians – the original quote from said politician (who shall remain nameless) was, "they're out to get me, it's a modern-day lynching y'all." This is a White guy, a white politician, an older white man. And, just a couple of days ago, he says aiding Black farmers with this COVID package is reparations. He was throwing around these words, "reparations," "lynchings," with no context, and making a victim mentality out of something that is generationally painful for people of color even to hear. So I wanted to take a stab at trying to show what lynching really felt like to those affected by it directly and show that you don't throw words like that around unless you know something about them. And in SILAS' case, specifically, although the methods may have changed over centuries, or over decades – the methods used to lynch – collectively, we still feel like we're victims of lynchings all the time. And they're severe and visceral even without the politics behind it. In the show, Silas (who's a victim of a real lynching) gets a chance to travel in time and see if it's any different 30 years from there, and then 30 years from there, and then 30 years beyond that. And he discovers that, yes, the world may have changed a little bit, but he still feels that same fear; it crosses generations.

In my experience as a theatre artist, all good theatrical art is an expression of identity. In what ways do you personally identify with the characters you've written in this play? And, maybe, in what ways do you differ?

I definitely connect with Silas. He's 30 when he's killed, and he's always kind of lamenting that he's just starting to experience his life when he's cut down in this prime. And that's the sort of thing which I experienced with my friends as a young adult. When I was 19, I lost eight of my friends to street violence, cut down in their prime. So I identify with that sense of loss. My life has been in danger a few times like that, so I know that fear. But despite that, Silas is optimistic, which I still am, too. And that's why he continues to travel, you know, when he doesn't see enough "progress" at each decade, he decides to move on. He's encouraged by each time period that he visits, but he's also discouraged by the lack of real progress. That's me in a nutshell. I've run the gamut in terms of my activism, from being a really fiery activist in my 20s to being more mellow and moderate now, but keeping that same fire for change. And hoping, trying to find any little sliver of optimism to say, "we've gotten better." It's definitely getting better, but I still feel that dread in the back of my head when I go to the grocery store. I gotta tell my family, "see you later," and blow my kisses because this might be the last time they see me. And that's true any time you exit your house, but being a Black man in America gives that thought a different connotation. When you say "be safe" to somebody leaving the house, it's not a throwaway line to us. With us leaving the house, it's real. That trip to the gas station might be your last, and it's sort of ridiculous in that way but also very scary.

As we've talked about, this script deals heavily with time, race, and justice. So now, moving away from your actor-centric relationship to the characters, in your experience as a Black playwright, do you currently (or have you ever) felt an obligation or pressure to create art that surrounds topics of race, justice, time, or progress specifically?

I do, but I embrace it gladly. That's sort of the reason that I started my own entity. There was a lack of that very thing, especially in Cincinnati theatre. You know, we all, as Black actors in Cincinnati got used to making jokes about "The Black Play" that was going to be in town that year. We would scour the local theatre companies and be like, "Oh, look, somebody is doing Jitney this year," you know what I mean? And it'd be like, "Alright, we all gotta fight for these five roles for African Americans" every single year. And your friends, these people you grew up with and shared a stage with for years and years, all of a sudden become competition because there's that one show with African American characters that happens to come in town every couple of years. And we'd see three years ahead of time, in 2012 saying, "They're gonna do Ma Rainey's Black Bottom in 2015, so we gotta get ready!" That's just sad as an actor to feel like you're wasting years and years for a single opportunity. So in part, I created Missing Front Plate to highlight works of color from artists in our town. We can rent out the venues that we want to perform in and do our own thing. And put more of that work and those stories on stage, so they'll be appreciated – and not seen as some rare event every time they pop in town. So as a Black actor, I've definitely felt that pressure. I'm going to emphasize works of color first and try to tell those stories that hardly ever get a chance to be seen.

Have you noticed an increase in commercial interest or demand for bipoc stories like the ones you're telling after last summer's protests?

Yes, they've started to hashtag and trademark it, which always worries me; when you see a copyright "c" in front of the activism, you gotta be worried. It becomes a tagline or a slogan. And yeah, I've seen a big increase in that because there was this reticence at first, you know? There was a demonization of BLM, "they're burning down cities and breaking things." And that seemed to be a nice cover for a while. But eventually, we had to reckon with our real problem of race in this country. I think more people were sincerely trying to change things, to change the way that we viewed race relations, especially creatively. But I think the inherent problem on a wider scale is that nobody knows how to approach it. And so any true allies, or anybody who really wanted to see change, didn't really know how to get their feet wet. It became "what can we do?" instead of taking the time to learn what to do. Let's get some history first, and then we can all meet in the middle– but that's not asking us, "what can we do to help?" It's been weird. And so it's translated into the hashtags. They found something that works, and now they're gonna make it their thing. Instead of being an organic movement, it's more like, "how can we capitalize on this and show people that we're not the racist ones" and all that stuff. Which is performative and infuriating, but I guess I'm glad to have people paying attention now. I mean, people are listening.

In your opinion, how much of this newfound interest for bipoc stories (within this Predominantly White Institution of theatre, and at Miami University) is earnest change-making? Versus how much is just tokenization?

I'm a pretty harsh critic about this stuff; I've just been dealing with it for so long. So maybe I'm a little harsher than I should be. But I tend to believe a good deal of it is still pretty performative. Only because people are fumbling in the dark, admitting that they haven't paid attention to these issues for years. You know, Dominique Morris, a great playwright, got together with all these other playwrights and theatre professionals and wrote "Dear White American Theatre" last year – that open letter. I read it and it inspired me. Every bullet point, I was like, "Yep, that happens. That happens. That happens." So over time, I think it'll resonate more. I think right now, it's the topic of the moment for theater-goers and theater folks, so people are trying to capitalize on it. But I also think there's an equal amount of pushback from activists, who are like, "no, that's not going to work, we're not going for that this time. Promoting us until it's not popular all of a sudden, then going to go back to your old ways". We're trying to make sure that this is a permanent change. So I'm a little harsher about it, but I'd say it's about 30/70 right now. 30 percent being sincere, while 70 percent is either fumbling in the dark or entirely performative. But we'll get there. I definitely want to bounce back on what you said about Miami, though, specifically in regards to SILAS. That was a concern, you know? They reached out and said, "Derek, it's gonna be kind of tough to cast." But they believed so much in the work that they were willing to say "we're gonna give it our best shot." And to that, I said, "do what you have to," because I could easily cast it from here. But I really wanted Miami to start some outreach and be responsible for the casting on their own.

Attend the MUT Digital Reading Series

New works that provide unique perspectives on our contemporary moment, shine a light on injustice, and share stories from underrepresented voices.

Please be advised that the series includes works that depict violence and trauma; audiences should review available information before deciding to attend a reading.

Youtube links to the shows in the Digital Reading Series can be found on the MU Theatre webpage.

Upcoming Premieres:

Sunday, March 21, 2021, 7:30 pm EST

Silas the Uninvited

by Derek J. Snow, directed by Daryl Harris

Silas tells the all-too-familiar story of a Black man in rural Louisiana who has just been lynched by a mob in 1930, yet finds himself mysteriously alive. In the events to follow, he is confronted with a choice to live again in another time as a Black Man in America and deal with some of the many complicated struggles with race and time that have always plagued this country.

Sunday, March 28, 2021, 7:30 pm EST

Describe the Night

by Rajiv Joseph, directed by Stephen Stocking

Set in Russia over the course of 90 years, this thrilling and epic new play traces the stories of seven men and women connected by history, myth, and conspiracy theories. In 1920, the Russian writer Isaac Babel wandered the countryside with the Red Cavalry. Seventy years later, a mysterious KGB agent spies on a woman in Dresden and falls in love. In 2010, an aircraft carrying most of the Polish government crashed in the Russian city of Smolensk.

These shows are currently live:

The Helpers

by Maggie Lou Rader, directed by Lindsey Augusta Mercer

The Helpers is a new perspective from the other side of the most famous bookshelf in history. Miep Gies, an immigrant, and secretary for Otto Frank's famous Opekta company, leads a group of helpers to preserve the residents of the Secret Annex and the spirit of goodness and survival during World War II. The Helpers is a tale of joy, hope, friendship, and resistance during one of history's darkest moments.

Baby Camp

by Nandita Shenoy, directed by Jenny Mercein

When Toni, Maria, and Aditi arrive at the Future is Freedom Retreat, they don’t know what to expect, but their fearless guide Lois is eager to share her plan to take back the power from conservative forces in government. Set in the not-too-distant future, Baby Camp asks whether adopting the playbook of the opposition is really the path to freedom and whether power is worth any cost.