Back Home Again

This 1994 was written by Claire Wagner for Miami's alumni magazine, Miamian.

Boston Globe Reporter Wil Haygood '76 seeks to rebuild the street of his youth, recapturing the life and the landscape through words.

Wil Haygood is coming off a long road trip to spend some time near his boyhood home.

The 1976 Miami graduate went to Somalia and India as a reporter for the Boston Globe. He made his way down 2,550 miles of the Mississippi River, part of it on a raft, to pen a tribute to America and Mark Twain. He traveled back in time to write an extensive biography of a nearly forgotten politician, and then visited 22 cities for book signings of the well-received work.

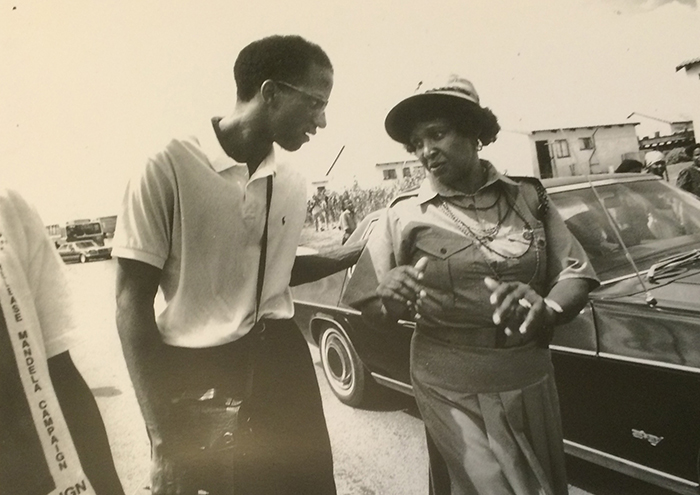

Wil Haygood walks alongside Winnie Mandela in South Africa in the days of hot demonstration before Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1991.

After all that, he's back this year in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. But he's not sitting still. Haygood is walking the streets and knocking on doors to uncover what still exists of the neighborhood that nurtured him and then seemingly disappeared.

It's for a book. Writing is in this man's blood.

Writing, however, wasn't in his schedule at Miami. The urban studies major took his first reporting job a year after graduation but then quit because the pay was so bad.

After trying at other occupations, Haygood decided writing was what he most enjoyed, and so he re-entered the world of newspaper reporting, pursuing and landing a post with the Globe in 1985. He's now on leave to produce his third book.

He wrote his second book, King of the Cats: The Life and Times of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (Houghton Mifflin, 1993), over six years of evenings and weekends. It was one he had to write, he says, to set the record straight about the man who put college within Haygood's reach.

Congressman Powell was known for many things: his flamboyance, his indictment on tax evasion charges, and questionable spending that cost him his committee chairmanship and House seat.

These items overshadowed Powell's lifetime achievements: his community activism that brought better housing and job access for Harlem residents, his Baptist ministerial skills that stirred and steered audiences, his ceaseless work for racial equity and integrated education that included Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty, and his co-founding of The Upward Bound Program.

While Powell was fighting to regain his House seat, Wil Haygood, a smart kid from a poor family, was attending a summer Upward Bound program, "a very encouraging and inspriring program" that he says prepared him for college and its challenges.

In 1972, the year Powell died, Haygood entered Miami. "The high school counselor didn't think I could get in."

Haygood was aware of Powell's negative reputation, but in 1979, he discovered the congressman's role in the creation of Upward Bound. "The scales of history were uneven. I asked myself, 'How could someone supposedly so bad do so much good for me and for other poor kids those summers?'"

"We were so poor when I was young, we not only had no bootstraps to pull ourselves up by, but sometimes no boots," Will told an audience during a Black History Month symposium at Miami last February. "I owed a debt to the man. "I'm trying to balance the scales."

Haygood received an Alicia Patterson Fellowship to support his research for King of the Cats. Critics like the book. Author Ward Just called King of the Cats "one of the best biographies of an American policitican in recent years" and proclaimed Wil Haygood "perhaps America's best young reporter."

Haygood's first book, Two On The River, published in 1987, recounted his journey down the Mississippi with Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Stan Grossfield, also with the Globe.

The book is an American essay in comfortable words and telling photographs that introduces readers to their Mississippi River neighbors from Minnesota to Louisiana, neighbors such as 80-year-old Leona Bunch in her garden.

"Everybody calls me Honeybunch," she told Haygood and Grossfield after they docked one night in Cape Girardeau, Mo.

Her dress was lime green. Nickle-plated earrings hung from her ears. She was not amused that we were traveling the river. Too many horror stories had fixed in her mind.

She patted her attractive auburn hair and said, "How in the world do you keep from the sun out on that raft? You know over at the hospital we have a lot of people with skin cancer. Catch it from the sun." Her eyes were glued to Stan's neck.

As we walked away she said, in the sweetest voice you ever heard, "I hope you boys don't drown."

Haygood's book are far removed from his reporting experiences at the Globe. "It was hard at first because you have to think a book out in a big, wide way. You can literally wear your feelings on your sleeve because it's your book and your narrative and you're shaping it.

"Of course, you must have a good book idea. You must have something that moves you, something that you really, really want to write about, something that you can't sleep at night for wanting to get up and write about it."

Once it was rebel fire in Bardera, Somalia, that kept Haygood from sleeping. He and Globe photographer Yunghi Kim were at an American Red Cross station in Somalia in 1992 when shots were fired, guards either fled or were killed, and rebels entered the compound. "You can't do anything. You go numb," Haygood recalls.

Fortunately, the rebels treated the journalists as neutral parties and agreed to let a U.N. pilot retrieve them. After 13 hours of waiting under armed guard, Haygood, Kim, and CARE workers were released in exchange for food and supplies.

Still, his strongest memories of covering poorer countries are not of guerrillas or dictators but of the humble populace. "They'll sacrifice to give you a good dinner, so you think well of them and their country.

"They're rich inside, and they want people to see that. These are people trying to raise their children and who lead ordinary and brave lives just by virtue of waking up every day."

Haygood's ability to see the profound in the ordinary has earned him literary recognition.

He was a finalist for the 1991 Pulitzer Prize and also has received a New England Associated Press Award, a National Association of Black Journalists Award for International Reporting, and a Sunday Magazine Editors Association Award.

Haygood is the 1994-95 James Thurber Fellow in Journalism at Ohio State University, where he will teach until March.

And so he's back home again, near Mount Vernon Avenue, researching a book that he says will be equal parts history, biography, memoir, and elegy. Set to be published in 1996, it will be "about a street in the middle of the state in the middle of the country," Haygood told The Columbus Dispatch.

He'd like to build it back up. That's what writers can do, bring life back to certain landscapes. Streets are histories, with flesh and blood. I'm a writer of tone. That's what I do best. I write about things that are missing, things that have fluttered away. It makes me happy to bring that back. And if people enjoy seeing that brought back, that makes me outrageously happy."