Journeys

![]()

By Margo Kissell

Mad at the rain, Tess Cassidy hiked fast. Painfully aware of the too-heavy backpack digging into her shoulders, she realized she hadn’t been happy in days.

She’d already conquered more than 1,600 miles of the Appalachian Trail. But she faced another 590.

If she stopped here, no one would blame her. Except herself.

Jackson Gray’s hands — sunburned from paddling on the Ohio River — tingled. Then they began to burn as if someone had poured boiling water over them.

Stroke by stroke, he extended his paddle deeper into the water so that his hands went under as well. Submerging them for brief moments temporarily eased the pain.

Gray was traversing all 981 miles of the Ohio River with Quinton Couch and Tyler Brezina in a canoe and kayak. The three friends were on a mission to raise awareness and funds for suicide prevention.

With donations flowing in and people following their Facebook page, they were determined not to quit.

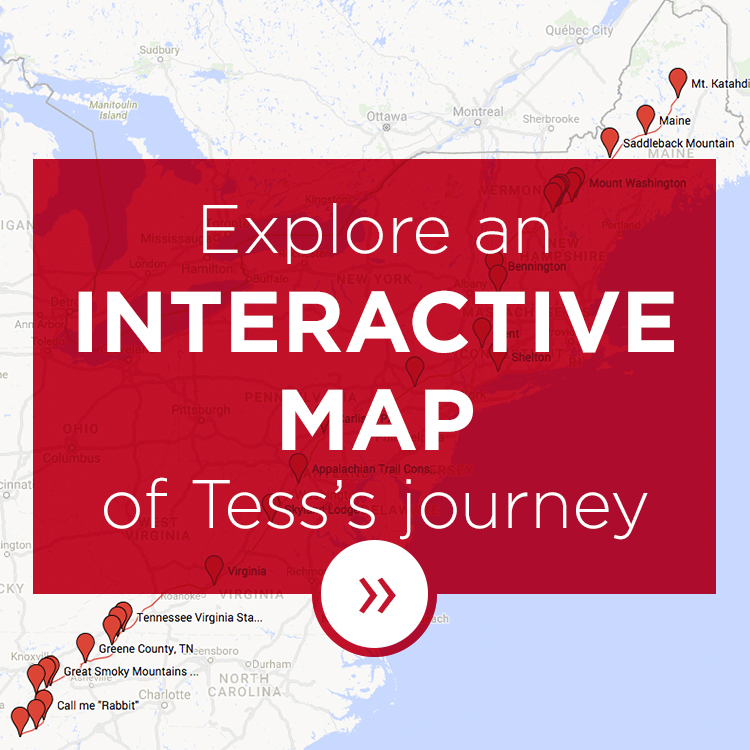

The Appalachian Trail and the Ohio River — two difficult, yet self-imposed journeys, each punctuated with tearful setbacks and fist-pumping triumphs, dangerous mistakes and clever solutions. These are their stories and their revelations — about the discoveries they made, both in themselves and in people they met along the way.

The Trail Beckons

Tess Cassidy graduated early from Miami University in December 2016 so she could hike the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail (AT) before starting her career.

Tess Cassidy graduated early from Miami University in December 2016 so she could hike the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail (AT) before starting her career.

Perhaps not an obvious pursuit for a woman who had backpacked overnight only twice before. The idea gained a toehold during the summer after her sophomore year while she volunteered for the Appalachian Service Project in Tennessee. On her days off from helping to improve substandard housing, she explored local trails.

Back at school, Cassidy drove herself hard. Majoring in supply chain and operations management, she made the dean’s or president’s list every semester in her three and a half years.

That time was, in her words, “go-go-go.”

By graduation, she longed for the physical and mental challenge of a thru-hike — a 160-day journey from Georgia to Maine. She needed to complete it before October when she was due in White Plains, N.Y., for her new job.

“I’m not looking to escape this lifestyle, but rather force myself to slow down,” the Dublin, Ohio, native wrote in her blog, Lost & Found on the AT. “On the trail I have one goal each day: hike.”

Racing the River

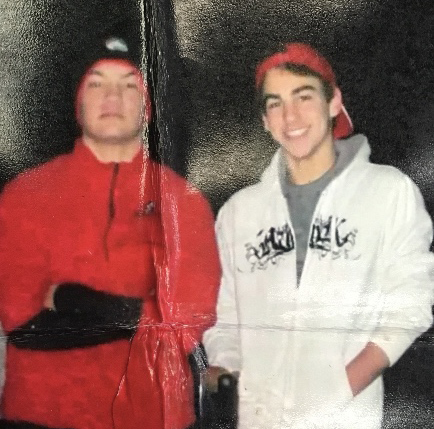

James Halley (left) and Jackson Gray in a photo Gray carried with him on the river journey.

James Halley was Jackson Gray’s best friend growing up in Canton, Ohio. They might have become lifelong friends, except Halley committed suicide as a college freshman in 2014.

For a long time after Halley’s death, Gray had a recurring dream of the two sitting at their school lunch table:

“If you feel like doing something, tell me right now,” Gray says to Halley. Responding that he doesn't know what Gray is talking about, Halley stands up and walks away.

Gray needed to honor his best friend. At the same time, the Miami senior majoring in civic and regional development wanted to launch a fundraiser that would call attention to suicide prevention.

Taking on the Ohio River became his focus.

Tyler Brezina signed on for the journey. Now a student at Bowling Green State University, he was on the same high school swim team as Halley and Gray.

Filling the third spot, Couch graduated from Miami in May 2017 with a major in diplomacy and global politics. He’d heard Gray talk about his plans as they steamed sandwiches behind the counter at Oxford’s Bagel & Deli. Couch, who has experience helping people struggling with mental health, respected Gray for his vision.

“It seemed like a really noble mission,” he said, “and a huge undertaking for someone our age.”

Joining a ‘Tramily’

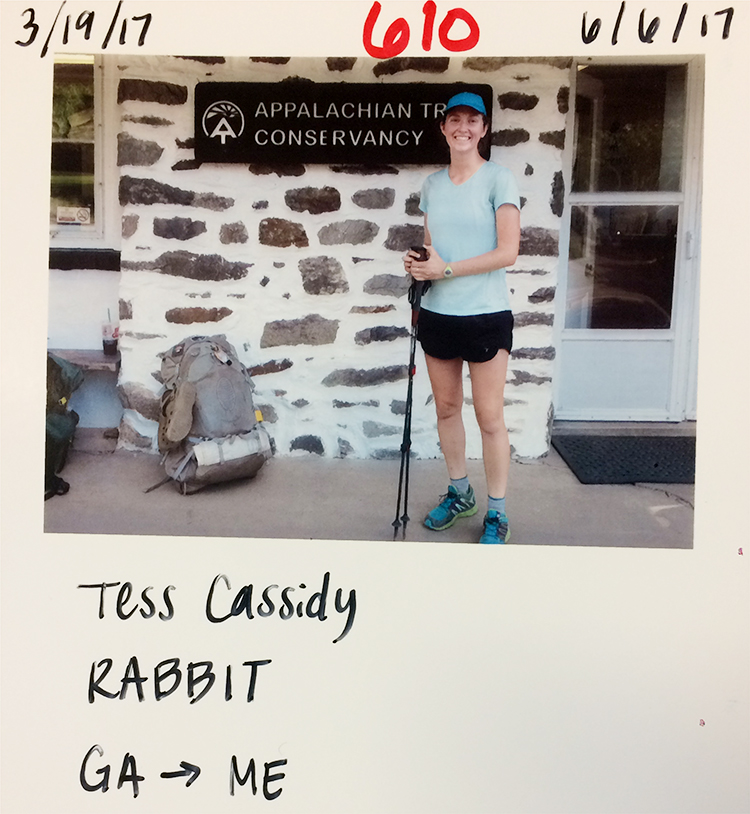

When Cassidy showed up on March 19, 2017, at Springer Mountain, Ga., she was greeted by Blue Ridge Mountains that had yet to shake off their brown winter hue.

Although only one in five who begins an Appalachian Trail thru-hike completes it, she found the southern gate to the AT clogged with optimists.

Her heavy backpack grew heavier after she added the first few days of meals she’d cooked and dehydrated. She planned to buy additional food while passing through towns, and her mom was going to send more dehydrated meals to pre-arranged mail drops.

Two friends from Miami on spring break joined her on the 9-mile hike to the first campsite, where they spent the night with 60 others. She was clueless about where to pitch her tent.

“That night, I was very scared of the dark even though a bear was not going to come near us because there were so many people.”

Cassidy’s friends and family could track her progress through her blog. There she proclaimed: “Join me in my journey of getting LOST in the power and beauty of the trail, & FOUND in who the trail molds me to be.”

As the miles accumulated and the number of hikers dwindled, she started to connect with others — Munch, Waffles, Minnie Mouse, Bunyan, High Noon. Hikers give each other nicknames for something notable. Her best trail friend earned “Velveeta” because of his cheesy jokes and brightly colored shirts.

“You camp near the same people at night,” she said, “and you end up forming what we call a trail family or a ‘tramily.’ ”

Cassidy became Rabbit when they arrived at a town after their first week in the woods.

“Everyone was excited about the Mexican food and the grill. I went to the grocery store and bought this huge bag of broccoli and carrots — no ranch dip, nothing — and just ate raw broccoli and carrots,” she said, laughing at the memory.

In the beginning, she was scared or nervous much of the time — more of people than animals and more in town than in the woods. She felt safest at camp, even though she often was the only female. Backpacking is traditionally a male sport.

The longer she was on the trail, the more empowered she felt. Struck by the beauty of nature around her, she recorded a poem on her phone as she hiked:

“It does not confine me, yet it shows me my limits. It humbles me, then it picks me back up. … There is no one to tell me ‘no’ out here. There are only the trees to show me how tall I can become if I stand the test of time — the tribulations of the seasons, strong winds and frigid downpours.”

Into the Water

At 3:30 a.m. on May 20, 2017, Gray, Brezina and Couch started a two-hour drive to Pittsburgh, where the Allegheny and Monongahela come together to form the Ohio.

Halley’s mother, Mary, pulled up as they were putting the kayak and canoe into the water. In tears, she hugged each young man and wished them well.

She then sprinkled some of her son’s ashes on the river so that he might join their journey.

Their first goal was to raise $7,000 for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention by completing the 981 miles in 40 days.

Their other goal was to start an important conversation about suicide, the second-leading cause of death among college students.

No Rain, No Pain, No Maine

Cassidy was consuming 3,000 to 5,000 calories a day, munching until she was full as she trudged north through 14 states, averaging 15 miles a day.

“I can’t eat peanut butter for the rest of my life,” she said.

She discovered that her decision to hike 830 miles, from Virginia to Connecticut, without a day off was a bad idea.

When a bite of her favorite chocolate caramel protein bar tasted weird, that should have been a red flag. Instead she packed it away and kept hiking. Although exhausted, she needed to make camp before nightfall.

When she finally arrived, she wanted to be alone.

“I took my mopey self down the steep, awful 0.5 (mile) descent to the water source,” she wrote in her blog. At the spring, she lay down and cried. The light rain added to her mood.

Suddenly feeling sick, she jumped up and sprinted as far away from the water as possible. After throwing up, she returned, filtered the water she needed and began a sluggish ascent back to camp.

Sick through the night, she was drained. To keep going, she played a game with music. Taking 10 hours to hike 11 miles, she could only rest after each song ended.

But that wasn’t her worst day. That day brought two hours of rain and thunder. Rain is the bane of most thru-hikers, explaining their mantra: No rain, no pain, no Maine.

She hiked fast because she was mad at the rain and the mud and a guy she didn't like, who was trying to keep up with her. She could hear his trekking poles hitting the rocks and roots behind her.

“What if I quit?” she asked herself. She left the trail and spent the day in town, seriously considering a hotel room for the night.

But pizza and ice cream strengthened her resolve. Determined once again, she headed back to the trail.

Unanticipated Complications

The guys mapped out places to eat, nap and camp for the night.

In West Virginia, they worked up the courage to knock on doors and ask if they might sleep in people’s backyards. Some flatly refused. Others were skeptical, taking a peek at their Facebook page before agreeing.

Two weeks into the journey, on their first day in Kentucky, a fun swim in the river to cool off turned serious when a piece of glass nearly severed the bottom of Gray’s right big toe.

A woman who had agreed to let them pitch their tent in her yard drove him to the ER for six stitches and strong antibiotics to stave off infection. Each morning, Brezina, an Eagle Scout, sealed Gray’s leg in a black plastic trash bag with duct tape to keep it clean and dry.

Complications still surfaced. Overwhelmed by the setbacks, Gray broke down in tears inside his tent. But he wasn’t about to quit.

“We were in it together,” he said. “We knew we were going to make it through come hell or high water.”

In addition to submerging his hands in the water while paddling, he wore a pair of tight gardening gloves he’d found along the river. They looked ridiculous, but the tightness provided pressure that eased the burning.

The day before they reached Cincinnati, the halfway point, a doctor told Gray to stop taking the pills prescribed to prevent infection. One side effect was sensitivity to light, and he was spending up to 12 hours a day in the sun.

Within two days, the pain subsided.

A New Season

The landscape transformed along with Cassidy. Once gloomy, it now teemed with life. Croaking frogs serenaded her to sleep. Singing birds woke her the next morning.

“The panoramic vistas show me how small I am in the world,” she wrote in her poem. “Yet, those same mountains I climb prove to me I can conquer anything. They show me even the largest hurdles to overcome can be tackled one small step at a time. The mountains empower me to take on the world, no matter how minute I may seem.”

Cassidy traveled more than half the trail with Velveeta, the upbeat young Pennsylvanian who enjoyed the rain.

“He knows me better than most people will ever know me,” she said, “because he’s seen me at my worst and my best.”

A Tragic Bond

![]()

The young men’s schedule developed a rhythm.

As they moved west, they rose at 4:45 a.m. They’d have sleeping bags rolled up, journals, books and other items packed in dry bags and breakfast finished so they could be underway by 6.

“It was orchestrated like a ballet,” Couch said, noting that Brezina’s scout experience was invaluable. “All the little things you don’t think about, like tying the rope up at night so you don’t trip over it. Getting a plan set for the morning. All the intricate details that saved our ass a bunch of times.”

Steve Siple (Miami ’90) of Birmingham, Ala., spotted their story on Twitter.

“As chair of the AFSP (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention) national board, I am so very moved to see this story from my alma mater. Well done, gentlemen!” he tweeted.

Siple lost his father to suicide in 2001. Struggling to find a “new normal,” he wanted something positive to come out of his pain. Living in Cincinnati at the time, he participated in one of the first Out of the Darkness Community Walks sponsored by the AFSP.

“I got involved at the local level there, and it’s just been a growing journey for me ever since,” Siple said. Like many other survivors, he found his complicated grief process focusing on “why.”

“You play back scenarios of the last time you interacted with the person, and you look in the rearview mirror looking for signs. You’re just constantly battling that desire to go back in time and prevent it. I think that leads to wanting to help others avoid that situation.”

Tragically, his is an all-too-common experience. All along the river, Gray, Brezina and Couch connected with people over the topic of suicide. No one seemed untouched.

After they set up camp in one family’s backyard, the woman asked if they needed anything. Walking back to the house, she paused, turned around and told them her brother had committed suicide.

“And that,” Couch said, “was the story every night.”

![]()

Our 'What If' Moments

After she reached Pennsylvania, her halfway point, Cassidy knew her body could hike 20 miles a day. But could her mind?

Mental exhaustion caused far more issues than tired feet.

“To be able to get up every day, take down your tent, get breakfast and then choose to hike 20 miles,” Cassidy said, “you have to want that.”

She did want it — bad.

Psychologists say most of us feel a compulsion, perhaps even an obligation, to take on challenges greater than ourselves once our basic and psychological needs are met.

Amy Summerville

Amy Summerville, associate professor of psychology at Miami, explained that we do this because we want to fulfill some sense of who we are and our purpose in life.

So we run grueling marathons, stress over starting our own businesses and spend years writing and rewriting book manuscripts — all to see if we can. Some even suggest it’s far better to fail than to regret never trying.

As director of Miami’s Regret Lab, Summerville studies the intricacies of this most common of our negative emotions, one we all deal with. She is analyzing when and why people focus on “what might have been,” and its effect on us.

“These thoughts have important influences on behavior,” she said, “and also drive the experience of regret, the negative emotion stemming from the realization that one’s actions could have resulted in better outcomes than actually occurred.”

Best of Humanity

Despite battling 14 mph headwinds and pop-up storms, the guys were progressing on schedule to Cairo, Ill., where the Ohio joins the Mississippi.

Their last night out, they set up camp and sat around a fire.

Only 20 more miles. It had taken them 41 days.

“That moment,” Gray said, ”we were the only ones who could truly grasp how momentous this trip was.”

They almost missed their finish line. Out on the water, it wasn’t obvious where the two rivers met.

“Remember how rough the river was that day?” Couch asked Gray. “I was thinking, this river is not going to give us one day. Not one.”

Their families were gathered at a state park to greet and congratulate them. Among them was a family they’d met from Paducah, Ky., who had lost a daughter to suicide.

“It was an amazing journey,” said Halley’s mom, Mary, proud of all they accomplished. “They got a lot of people talking, and I know they raised quite a bit of money.”

In the end, they collected $10,000, surpassing their goal by $3,000.

But the money was only part of their outcome. Their adventure was filled with awe-inspiring moments under the stars and poignant conversations with people touched by suicide.

“The collective humanity along the Ohio River really did it for me,” Couch said.

Reaching the Summit

For Cassidy, approaching the end of the trail on Aug. 25 posed its own special challenges.

She met back up with Munch and Velveeta for the final 3-mile climb to the top of Mount Katahdin in Baxter State Park.

“At first you’re in the trees and it is kind of hard, then some larger boulders start appearing that you have to climb over. Then, when you have to skirt above the tree line, you have a view for miles of all these lakes in Maine but,” she said, laughing, “you have to rock climb that section.”

Didn’t matter. Nothing could stop her now. When they reached the sign marking the end, all three kissed it at the same time.

“It was one of the best days of my life,” she wrote in her blog. “The day was full of triumph, emotion and sad goodbyes to lifelong friends.”

She called the journey raw, rewarding and full of joy. She thought she could put into words what reaching the summit meant but realized the summit wasn’t a moment. It was a five-month test of her resolve.

Weeks later, she choked up talking about the people, the memories and the end. The trail will always be a large part of who she is and who she becomes.

The experience gave her a newfound sense of calm, something Cassidy noticed near the finish in Maine. It was nighttime, a thunderstorm was approaching and she was by herself in the back country miles away from a road.

“I was very at peace and very comfortable. I wasn’t nervous at all about being alone in the woods.”

Where Are They Now?

Tess Cassidy is in the leadership development program at DanoneWave, formerly Dannon Co. She is a deployment planner in the company’s White Plains, N.Y., headquarters.

Jackson Gray, who takes classes on Miami’s Hamilton campus, graduates in May. He plans to move to Austin, Texas, in June to work as a national account representative for Arrive Logistics, a supply chain services provider.

Quinton Couch recently completed a fellowship through Chicago Votes, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization, in which he led a service-learning project at a Chicago high school.

Tyler Brezina is a sophomore majoring in aviation at Bowling Green State University.

Suicide Prevention

If you suspect someone may be at risk, call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255).

For more tips and warning signs: American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Student Counseling Service

At times, everyone feels stressed, angry, depressed, anxious or confused. If you'd like to talk to a counselor, call 513-529-4634.

Miami's Mental Health Ally Program

The volunteer program, coordinated through Miami's Student Counseling Service, offers education for faculty, staff and students on how to engage students experiencing emotional or mental health concerns and refer them to mental health and other support services.