Understanding the Science Behind Stress and Self-Care with Dr. Vrinda Kalia

This past year we’ve all, in our own ways, become something like experts on stress. Or at least experts on feeling stressed out. And while that feeling may often be a weary and helpless one, attendees at the final installment of the Howe Center for Writing Excellence’s “Self-care in Times of Stress” series learned that there are ways to forge a more positive relationship with stress. It starts by understanding the science of stress, and then prioritizing your own self-care.

Dr. Vrinda Kalia, an assistant professor of psychology, led the virtual workshop. Kalia is quite literally an expert on stress. She runs the Thought Language and Culture (TLC) lab here at Miami University. Under her guidance, an interdisciplinary team of psychologists, biologists, and physicists investigate how culture, emotion, and motivation impact cognition. Stress is at the heart of their research.

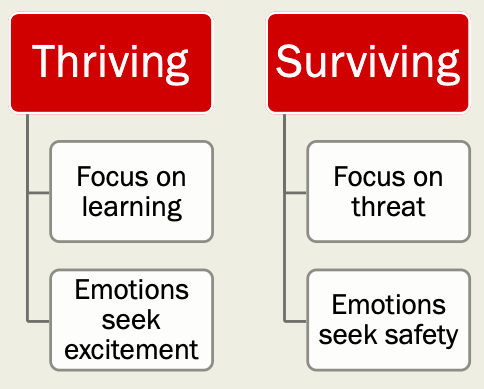

Stress isn’t a monolith, Kalia points out. And it isn’t all bad either. “Positive” stress is stress we can encounter with the expectation of growth and control. It brings about a brief increase in heart rate and a mild elevation in stress hormones, which both recede to normal as you recover. The work that your body has to do to bring you back to normal after stress is called allostasis, and a healthy amount of it will help you manage similarly stressful situations in the future. Your body effectively “learns” a proper response as the positive stress gets processed in the cortex, a cognitive area of the brain. Positive stress is proof that stress doesn’t always have to overwhelm us. It can actually help us thrive (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Conversations around stress often focus on surviving, but with

a “positive” response it’s possible to thrive while experiencing stress.

If you’re thinking that your own recent experiences with stress have been far from the “thriving” model, Kalia can explain the science behind that, too. When you face intense, prolonged, uncontrollable stress (e.g. the past year of pandemic), allostatic load builds up as your body works harder and harder to help you recover. Called “toxic” stress, this variety puts your body into a near constant state of activation, disrupting allostasis and making recovery difficult. “Toxic” stress is processed in the lower areas of the brain, which are associated with emotions and involuntary responses. You aren’t “learning” from this sort of stress. Rather your body is perceiving a threat it feels it must retreat from. You are “surviving” the stress (Fig 1).

Stress weighs heavily on emotions, and emotions weigh heavily on perception and behavior. So the impacts of stress compounded over time can be substantial. Consider this article recently published by the TLC lab, authored by Kalia with contributions from graduate students Katie Knauft (who's also a Howe Writing Center consultant) and Niki Hayatbini. Analysis of survey data from 350 people showed a correlation between early life adversity and one’s perceived threat from COVID-19. In other words, people who lived through stress-inducing situations when they were young were found to be more likely to feel stressed and threatened by the conditions of a global pandemic. For many people studied, experiencing early-life stress appears to have become an enduring expectation of stress.

Fig. 2. Dr. Kalia and her research team at the Thought Language and Culture (TLC) Lab.

You might now be wondering, is it possible to break through a negative pattern of stress?

Well, that’s a complex question, and certainly contingent on factors unique to the individuals experiencing the stress. Again, stress is not a monolith. While our response to stress can depend on how we internally process it, it’s also true that we experience plenty of external sources of stress not at all under our control. Kalia’s aforementioned article is a testament to that. As is research showing that social hierarchies in workplaces influence stress, with employees furthest removed from decision-making and holding less secure positions at increased risk for stress.

You may not be able to control external sources of stress. However, by taking some measures to control your internal sources you’ll be giving your body a better chance to adequately respond to stress and then heal in its wake.

Calibrating expectations for yourself in times of intense stress can make a difference. So can practicing intentional self-care, which Kalia frames the benefits of by using a simple analogy. When you travel on an airplane (remember that?), what’s one of the most important points flight attendants make during their review of safety procedures? In the event that the cabin loses pressure, you put your own oxygen mask on first. The idea is that by taking care of yourself, you’re in a better position to take care of others. It’s an insight to keep in mind as we continue to live through this pandemic, and its impacts, the best we can.

Here are a few of Dr. Kalia’s best practices for dealing with stress.

- Manage expectations, including lowering them in times of intense stress.

- Know your triggers and red flags.

- Be compassionate to yourself first — and then don’t forget to pass it on.

- Stay connected to others.

- Partner with a therapist (Miami offers resources and counseling services, and mental health visits may be covered by your Miami health plan).

- Seek social support at work.

Looking for opportunities to self-care as the semester draws to a close? Join us at Chair Yoga for Writers, every Thursday afternoon (3:15PM–3:45PM) and every Friday morning (11:30AM–12:00PM). Attendees must sign a waiver, so before your first session please fill out this form. We’ll then provide you with a calendar invite.