Winners of the HWC's Spring Writing Contest

In March, the Howe Writing Center (HWC) invited all Miami writers to enter Luck + Chance, a creative non-fiction writing contest. Participants shared stories about when luck or chance played a role in their lives. HWC writing consultants and staff chose four winning entries from the anonymous submissions.

Meredith Perkins was awarded first-prize for her piece “Clovers," which explores not only the rarity of these good luck charms but one’s own individuality.

Sofia Rakic’s “Tablić,” which earned second prize, offered a reflection on childhood games and the lessons learned from family.

Olivia Kelly, third-place winner, investigates the loss of cultural identity joys in "Canip and Pain."

JoAnn Su, the staff choice winner, reflects on the meanings of luck in the poem “Doubt and Recovery" and its sequel "From The Other Side."

Read the first, second, and third-place winning entries below.

First Prize: Meredith Perkins, Clovers

For my piece, I decided to synthesize my childhood experiences looking for four-leaf clovers with my childhood experiences being diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder. The topic idea came to me because I wanted to put a different spin on the idea of luck; I wanted to show that luck or being special can bring obstacles. I enjoyed grounding my piece in the metaphor about clovers because I really liked clovers as a child and, of course, clovers are a symbol of luck!

Read, Clovers

I used to think that Wednesday was the first day of the week.

That 1,000 was the biggest number; that dinosaurs lived in Kentucky; that Santa Claus answered my prayers; that chocolate milk came from chocolate cows. Before I knew how to tie my shoes or braid my hair, I saw the world through the glittery, misguided eyes of a bashful four-year-old girl. I loved fantasy and folklore and fiction and fairy tales; movies like Tinker Bell and A Bug’s Life that made nature seem infinitely majestic.

I didn’t grow up in mythical forests or magical bug kingdoms; I grew up in Independence, a town where the primary vegetation is mowed grass and clumps of deciduous trees along highways. In my yard, my family had a crimson-leaved Japanese maple tree, a fruit-filled pear tree, and clumps upon clumps of clovers.

In the Middle Ages, children loved four-leaf clovers because they believed clovers let them see fairies. Ancient Irish Druids held similar beliefs about clovers; they saw clovers as magical charms that would protect them from bad luck. As a little girl, I misunderstood these legends. When the clovers bloomed in the spring, I would pick through the clover patches in pursuit of a lucky three-leaf clover.

Of course, I had no trouble finding three-leaf clovers in my yard; for every four-leaf clover on earth, there are 9,999 three-leafed ones. Whenever I stumbled upon a patch of perfect three-leaf clovers, I felt like a pirate who had uncovered the ultimate buried treasure. The odds of finding this is one in a bajillion. I’m the luckiest kid alive. When their little girl raced into the kitchen grinning ear-to-ear rambling about the clovers she picked, my parents couldn’t help but smile and hug me and tell me that’s great! That’s awesome! In their arms, I was the luckiest child in the world.

When I would play outside, my knees would scrape, my shoulders would slide out of socket, and my arms would bend backwards. I knew there was something different about me, but I couldn’t figure out what made me special.

Four-leaf clovers don’t occur naturally in the wild; rather, they are caused randomly by a genetic mutation. Aside from the physical mutation, a four-leaf clover is virtually identical to a three-leaf clover. They attract the same predators, grow in the same habitats, absorb the same sunlight, bloom in the same seasons—from a distance, a four-leaf clover appears identical to the other three-leaf clovers in its patch.

Growing up, I was just like every other kid: my hips clicked on the balance beams during gymnastics practice, my shoulders slid out of socket when I dove into the pool at swim practice, my wrists popped out of place when the old church ladies would shake my hand at Sunday services.

I had the normal growing pains of any elementary schooler. I laid in the bathtub and sobbed while my legs throbbed, staring into the shower tile and begging that I get diagnosed with something, anything so I could learn why I felt so horrible. I developed tendonitis in both arms after a swim practice. I dislocated my shoulder on field day and popped it back into place like it was no big ideal; just a normal Friday afternoon.

It was a normal Friday afternoon. I was fourteen, sitting on the white, waxy paper of the rheumatology exam table. A man with a Santa Claus beard and wire-rimmed glasses was bending my arms, bending my wrists, and bending my legs.

20 degrees hyperflexible in each elbow.

15 degrees hyperflexible in each leg.

8/9 on the Beighton score.

I was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome type III, a connective tissue disorder that causes joint hypermobility, chronic pain, muscle weakness, and frequent dislocations. My disorder is caused by a mutation. It can occur in anybody, and in most cases, people don’t know they have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome because they assume their joint problems are normal.

I felt unlucky when I was diagnosed, but the Irish legends of the four-leaf clover remind me that there is beauty in being a mutant. In Irish culture, the mutated clover represents faith, hope, love, and success. Mutations aren’t burdens or curses; it’s a special kind of magic that makes me stand out from the rest of the patch. I wasn’t born normal like the three-leaf clovers I loved as a child, but that’s okay. Back then, I misunderstood plenty of things: the calendar, the numerical system, how cows created milk—even the nature of my own body.

Now that I’m older, I finally understand my condition. I understand how to adjust my lifestyle and activity level to better take care of my joints. I understand that if I bend my arms backwards at a party, I shouldn’t bend them too far or else I’ll have a show-and-tell incident. I understand there’s something truly fascinating about being born with something that less than 1 in 20,000 people have.

There’s truly magic in being rare.

Second Prize: Sophia Rakic, Tablic

My inspiration came from the nights I spent at my grandparent’s house. As the daughter of first-generation immigrants, I am grateful for the sacrifices my parents made that have allowed me to be where I am. I am lucky to be here. However, despite that luck takes, not only skill, but genuine reliance on my loved ones to raise me, teach me, and develop me into the individual I am today. Aside from the language, recipes, and histories, I have learned games. I have learned to press my luck, exercise my skills, and rely on others' aid in order to thrive. This relational element is often forgotten in games, as we become so immersed in competition, we forget to acknowledge those who we wish to win for.

This piece was a challenge because I wanted to capture the in-the-moment tone that reflected the gameplay of Tablić. Likewise, I wanted to show the growth I had in both gameplay to understanding luck vs. skill from childhood into my early adulthood. I hope to cultivate this piece further into a shorter work of prose and expand on other relational elements of Tablić and my childhood.

Read, Tablic

Deda exhaled through his nose, half-smiling. “Tabla!” he declared and swept the cards off the table.

Baba put me to bed that night. I pouted that Deda had all the luck in the world and I just wasn’t good at Tablić. I thought about how it wasn’t fair that Baba and Deda were six times as old as I was, so of course they were going to be much better than my brother and I were. They had all the lucky cards and years of skill, so of course they had won.

Tablić, as I’ve learned, is a fishing-type game. Not like “Go Fish!” or another juvenile card game; rather, the rules are more complex. There are four players with two fixed pairs that sit across from each other at the table. My brother and I always sit across from each other and Baba and Deda the other pair. One cannot communicate with their partner during the game, but mutual effort is needed to win.

Deda starts the dealing. We all receive six cards at random to start. He cuts the remaining deck and slaps four cards face-up on the table. A Queen, 6 of clubs, 8 of spades, and 4 of clubs.

I scour over the cards in my hands. I have a 10, 8, 4, 4, 2, and a 9. I grimace at my brother. I got a really lousy hand, I silently lament.

Suits really don’t matter. A 4 is a 4 and a 7 is a 7. Kings are worth 14, Queens are 13, and Jacks are 12 points. Jokers are thrown out. Aces can be high or low as the player chooses. Whatever cards I have in my hands, I must choose one and pick up either a card of equal or summed value off the table. My 10 could be the 6 and 4 or a 4 for a 4, so I pick up the 6 and 4.

I picked up three cards, but I only gained a single point because just faces and 10s are worth one point. When a player sweeps the whole table, they must declare Tabla! and are given a bonus point.

I leave a Queen and a 4 on the table. Baba looks agitated. It seems that she doesn’t have a Queen or four; so instead of picking up a card, she must forfeit a card down on the table: she releases a 2.

“Aha,” my brother declares and uses his 6 to take 4 and 2.

I want to kick him under the table and cry out for him to stop! Nevertheless, he picks up the two cards, joins them with his 6, and neatly places them in a pile off to the side. No, no, no! Now he has left the Queen on the table without a defense against the chance of a t–

“Tabla!” Deda calls out and sweeps the Queen off the table, sticking her to the Queen that was sitting in his deck. Baba and Deda now have three points, one for each Queen, and then a bonus for the Tabla. Deda laughs, “good job, Baba.”

Still, I love Deda’s laugh and my spot at the kitchen table. I’m lucky that my grandparents lived so close. Their house was warm and Baba made good food. Deda taught me how to garden, how to speak our language, and play games. I became skilled at chess because Deda refused to let me win. Sometimes we

played casino games and only I won because of luck that fell into my favor. But after dinner, we liked to play Tablić.

I know why Deda said, “good job, Baba.” Baba was probably dealt a lousy hand. She knew that my brother would eagerly scoop up easy cards. There was a chance that if she did that, and my brother took the bait, even with her lousy deck Deda would have a Queen and they’d get tabla. And he did.

It certainly was not luck or skill alone that they won, nor some sort of luck-plus-skill thing. Winning was not alone, but an implicit reliance on others to analyze the sort of luck we’ve drawn. I have played Tablić hundreds of times now and, as luck may have it, I have been dealt many rotten cards. I look to my partner across the Tablić table and hope they see my eyebrows furrow and implicitly ask for help. Even with all the luck in the world and the most sparkling suits in my fingertips, without the support from my partner, I am no closer to winning a Tabla! than I am to forfeiting my King onto the table.

Third Prize: Olivia Kelly, Canip and Pain

I changed the name in the document to one other than my own for anonymity's sake, but everything else is true. The piece is about being a second-generation American Latina, the unfettering from generational fear that comes with that but also the loss of identity-specific joys. In being too cautious, too rapidly assimilated, too ready to accept safety lies the possibility of losing both my family's identity and the pleasure possible when I embrace it.

The bolded bits within the piece should be taken both as one sentence and as the titles of each section they head. The list in the middle is of the different names for the same fruit across the Caribbean and the world.

Read, Canip and Pain

I am allergic to fruit. The doctor told me I was allergic to uncooked pitted fruits, “all of them?”

“Yes, all of them.” when I was 12 or so. Almost ten years with peaches, plums, avocados, cherries, all of it forbidden to me.

Despite what she said, I do not want a life lived without risking pain for joy. My mother tells me to stop chancing it every time. “You could go into An-a-phy-lac-tic shock, daughter!” She likes to punch the words out over the phone. She calls me Sara-ma and not daughter when I am more responsible.

The Head must suppress

The feeling she is trying to protect me from ranges, anywhere from a tickle you could mistake for sourness to closed throat panic. In a house with no benadryl, you suck down water and lie down on your dad’s couch until you can go home. Sometimes the feeling betrays you, and things that you thought were safe are suddenly not. Sprite, for example, is not as processed dead as one would think. Despite Monsanto’s best efforts, lemon lurks, and it coats your throat with phlegm until you stop ordering shirley temples. If all fruits are dangerous, probably so are all sodas. Order water and spare the expense. Coughing at the table is rude.

The Tail’s desire

Have you ever had canip?

Have you ever had ginnip?

Have you ever had mamones?

Have you ever had limoncillo?

Have you ever had quenepa?

genip, guinep, genipe, ginepa, kenèp, quenepa, quenepe, quenette, chenet, skinup, talpa jocote, mamón, limoncillo, canepa, skinip, kenepa, kinnip, huaya, or mamoncillo?

It’s a fruit without a name, and too dangerous to taste again. They sell them on the ramps up to the highways in the Bronx, waving them in the air so the People On The Move can see what they mean, and supply the right name in their own language. When I was younger, my ma would slow the car and buy mamones in Spanish that marked her as too long gone from the islas to be catracha, for real, anymore. Waiting to take them home was torture. But we had to wash them first. They’d come from who knew where in the wide Atlantic, and they’d been here in the city for who knows how long. They were dirty, had to be. So we’d rub vegetable wash into the green leather skins until we had a good suds. Then we’d rinse, and the anticipation would be too great to let them dry. Kenip doesn’t come every year. I’d crack them with my molars as my mother or grandmother or tante laid them out, done with helping. You can still feel the cool pebbling of the skin with the midsection of your tongue. You can have almost any produce whatever time of year you want, now. Apples, pears, oranges, frozen rhubarb and fresh strawberries, all these have come unmoored from time. The nameless has not. Bound to three weeks of the New York summer, to close your lips around one of them is to taste coolness itself. The skin, firm, textured and tasteless, has taken the temperature of the water it was washed in. Then you split the skin with your teeth, and there it is. Yellow orange flesh, sour on your tongue. The flavor, too, is as nameless as the fruit. There are no comparisons to make, no fitting similes. How would one describe live music on a dark beach to someone who has never felt night air? You’d say it’s sweet, and bright, and a little sour: something to be afraid and in awe of even as you luxuriate in it in a joy beyond life. The fruit reminds me that our island is full of isla, and I still belong to both.

I’m slowly realizing I’ve lost both to my sensitivities. And so my body begins to choke me, prickling fingers reaching past my lips down my throat to that too-shallow well in the chest where tears are held. Still, I swallow the fruit past the swelling of all of it - the panic and the throat and the tightening breath. I spit out the pit ptah and my fingers twitch for another.

Mama-ma mía, taste this again and please try to tell me some things are not worth risking.

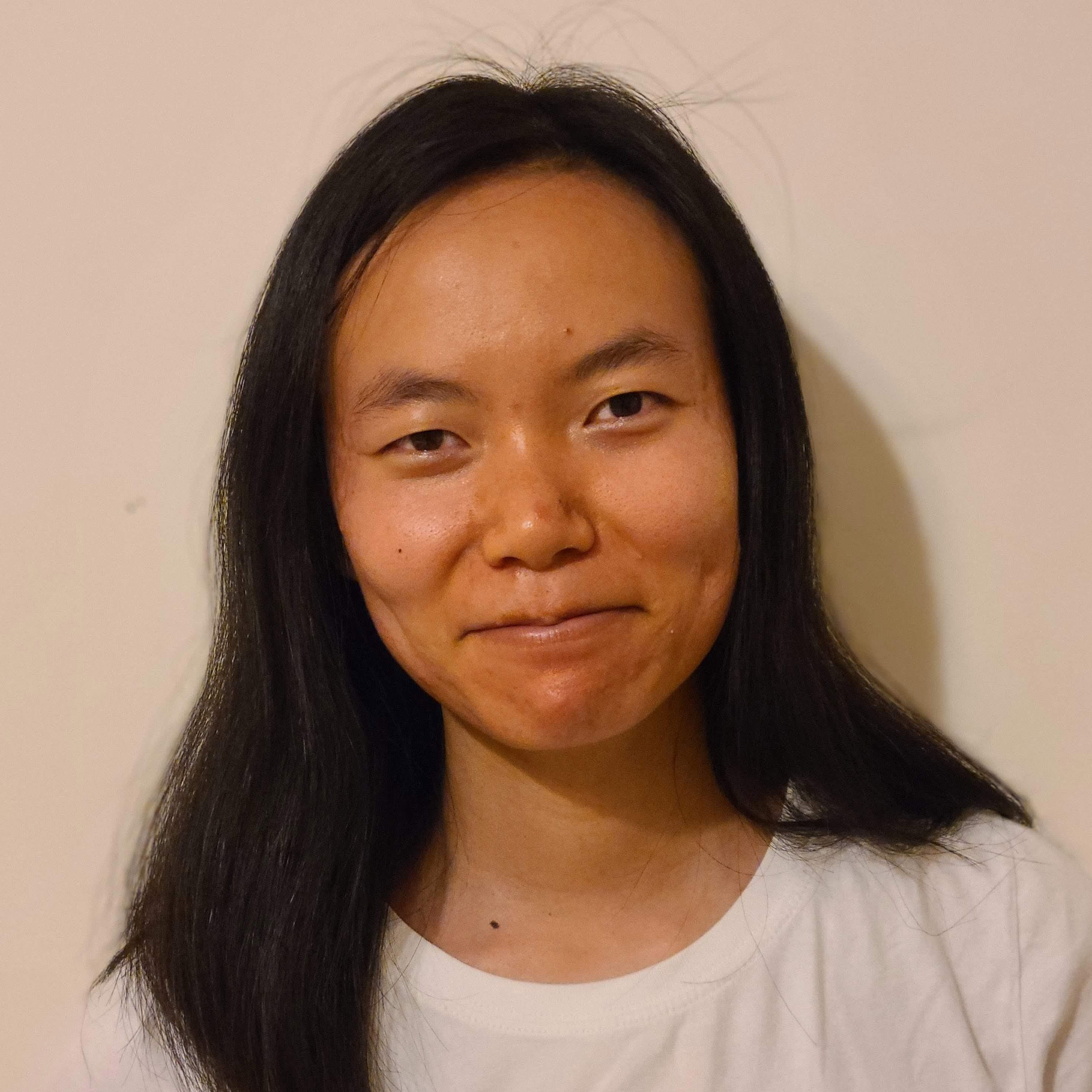

Staff Choice: JoAnn Su, Doubt and Recovery/From The Other Side

“Doubt and Recovery” delineates the first few years of my undergraduate studies. I began this journey very apprehensively due to an extensive four-year complication with mental disorders and diagnoses. These diagnoses especially brought in a lot of self-doubt when I was a freshman, and as the reader will later note, I was essentially a freshman for four semesters due to my credit hours and other struggles. These struggles were not just academic; they were social, emotional, mental; my life was completely out of control due to the manifestation of my illness. “Doubt and Recovery” relates to luck in my shift from finding myself to be unlucky to transitioning to asking myself, “How can I be so lucky?” The poem narrates what led to this transition.

“From the Other Side” is a sequel, per se, to “Doubt and Recovery.” It continues the narration but in a more timeline format of listing what years had what events that relate strongly to how luck has played out in my life. These years recount two deaths of loved ones and finishing undergraduate studies in the midst of the outbreak of the coronavirus. I address racism and how I seemed to get lucky. The poem proceeds to outline my experience in finding a teaching position in the midst of unrest from the pandemic followed by my acceptance into Miami University’s Graduate School. I conclude with the hope mentioned also in “Doubt and Recovery”. The hope seems to have resurfaced and embellished within the seven-year time frame between the beginning of “Doubt and Recovery” to the present day, or the end of “From the Other Side.”