Hardship or Hope? Miami students study the American Dream in small-town Iowa

By Shavon Anderson, university communications and marketing

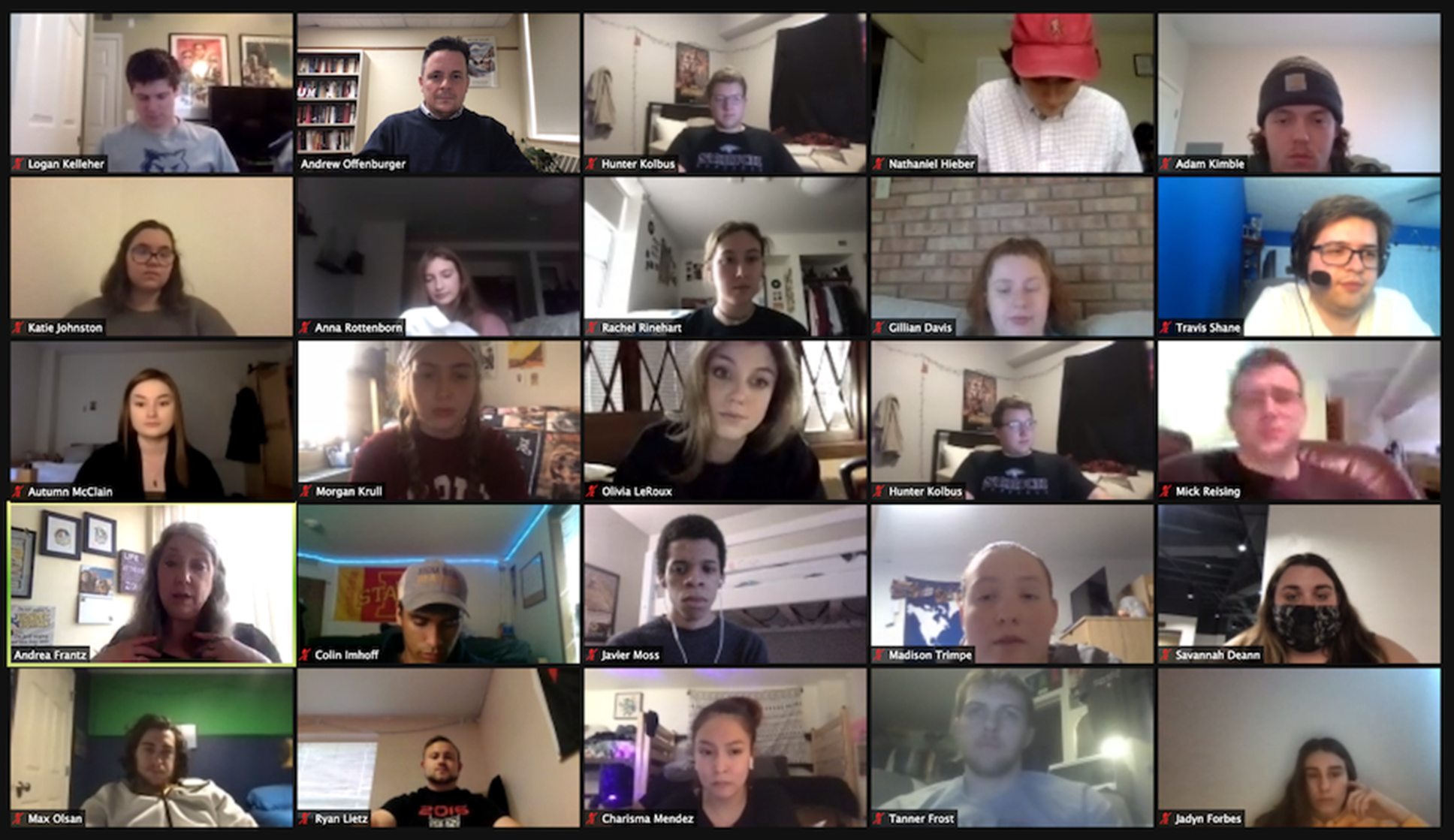

Contributions by Andrew Offenburger, associate professor of history, Olivia LeRoux ’21, Justin Hobart ’22, and content from "Researching Midwestern History"

Matthew Marroquín

As a Hispanic kid growing up in Storm Lake, Iowa, Matthew Marroquín had no concept of race.

“I just knew that if I go over to this friend’s house, I say ‘hello’ to their mother in this way, and if I go to a different friend’s house, I had to learn ‘sabaideebor’ for Laos, or ‘xin chào’ for Vietnamese,” he said.

When he was still a baby, his family moved from Los Angeles to Storm Lake so his father could work at the town’s meatpacking plant. His father spoke little English, his mother barely spoke any, and Marroquín picked up “Spanglish” to chat with friends. By the time he reached high school, he began to realize just how unique Storm Lake was. Neighboring schools would send their students over to take “diversity tours.”

“They were surprised that we didn’t have police walking around all the time, and that we all sat together during lunch,” Marroquín said. “That was the biggest thing: that we actually, you know, were integrated.”

Today, Storm Lake residents –– upwards of 50% Latinx, 30% Asian, and 20% White –– speak more than two dozen languages. And on the front page of a 2017 New York Times profile, a headline summarized contemporary Storm Lake: “In Rural Iowa, A Future Rests On Immigrants.” Now a student at the local Buena Vista University, Marroquín shared his story with Miami University history students as the class embarked on a semester-long research project: Has Storm Lake found a way to reconcile the real world with the American Dream?

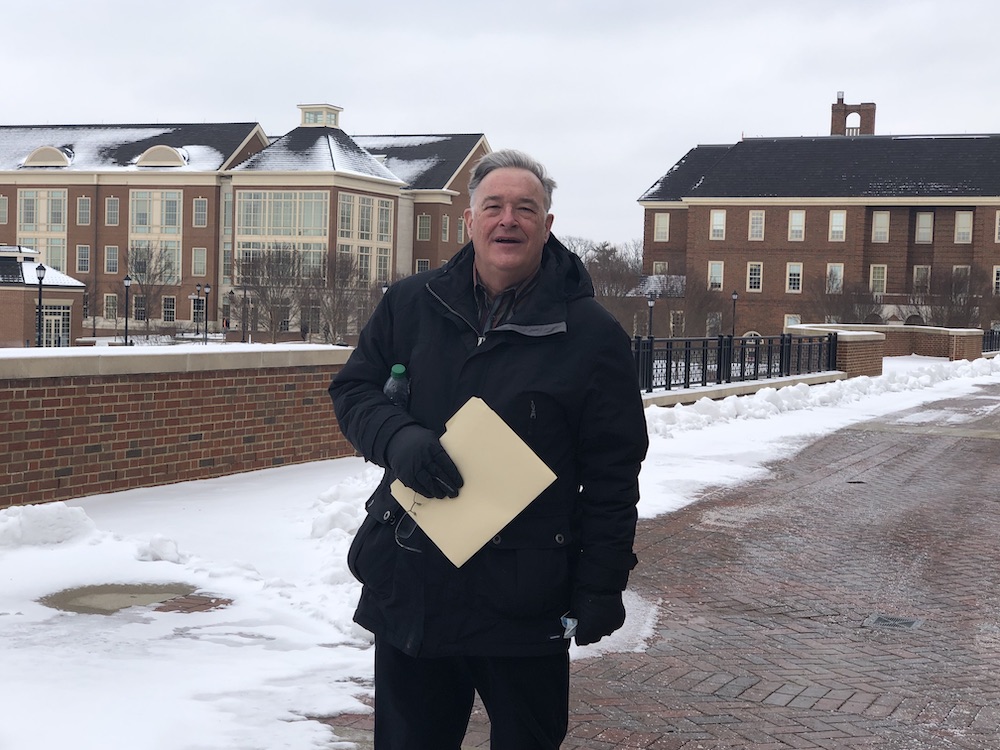

Studying Storm Lake was intentional, but the timing came unexpectedly. Faculty lead Andrew Offenburger, associate professor of history, graduated from Buena Vista in 1998 but, back then, didn’t realize how globalization shaped the town around him. It wasn’t until two years ago, when his Argentinian wife María became a U.S. citizen, that he thought more systematically about the stories of others working toward a life in the U.S.

“By now you can understand why I, an Iowan who has witnessed immigration firsthand, have been drawn to Storm Lake more and more,” Offenburger said. “I feel vested in the community. All Americans should.”

As he stood alongside his daughters and listened to María recite the Oath of Allegiance in a Cincinnati courtroom, he wanted to understand the historical shifts within Storm Lake and to document the journeys of its families. The opportunity, and a $5,000 grant, came during the 2020-2021 school year when Miami launched the latest phase of its award-winning program, HumanitiesWorks. Aimed at connecting classrooms with communities nationwide, the initiative encouraged faculty to explore the value of current degree programs and develop problem-based, experiential elements for existing courses. With funding, Offenburger structured his course, “Researching Midwestern History,” to produce humanity-driven outcomes–– leaning on student interaction and interviews with residents, community leaders, and experts, pushing tough group conversations, and ultimately delivering an oral history based on themes connected to labor, migration, and identity.

Finding authentic narratives

Michael "Doc" Whitlatch '73

There are about 20,000 residents in Storm Lake, a town 2.5 hours northwest of Des Moines. Michael “Doc” Whitlatch ’73 likened old Storm Lake to a 1950s sitcom –– “Leave It to Beaver” or “Father Knows Best” –– with a population of mostly white families living simple lives. Whitlatch, Professor Emeritus of Performing Arts at Buena Vista University, spent 39 years in Storm Lake after graduating from Miami and joining Buena Vista’s faculty in 1977. Soon after, he and his late wife, Jean, a school teacher, witnessed the height of immigration.

Whitlatch, who retired to Dayton, Ohio, met with students early in the semester to provide background on the community and explain how, with a sudden influx of workers from Mexico and South Asia, Storm Lake absorbed diversity.

“The doctors’ offices have gotta adapt to the businesses in town. Banking and auto and the grocery stores all had to change,” he told students. “The [job seeking] ads in the paper reflected the changing nature of the town.”

Using Whitlatch as a foundation, Offenburger’s class investigated Storm Lake between 1970 and 2020, looking into topics like politics, education, economics, and policing. Weekly assignments required analysis of town newspapers, and a slate of more than 40 Zoom interviews –– with health advocates, city council members, presidents of universities, and activists –– provided wide-ranging perspectives. The class published a blog, “Researching Midwestern History,” to document their findings.

The idea wasn’t to paint Storm Lake as perfect but to understand how aspects of the community’s work can be modeled nationwide.

“We examined the good and the bad and how those meatpacking industries built this town,” said Olivia LeRoux ’21. “What are they doing right? How are they able to create this strong sense of community?”

In conversations with school district superintendent Stacey Cole, Cole described how administrators and teachers completed anti-bias training and revisited policies and hiring practices to better serve families who spoke dozens of languages.

A later interview with Cole’s husband, Police Chief Chris Cole, revealed language barriers and gave insight into the initial culture shock officers faced:

[Cole] recalled one of his first days on the job when he had chased down and tackled a man. Upon identifying him, a Hispanic man with the name Jesús, Cole declared, “You’re in trouble now Jesus!” (Cole had used the Anglo pronunciation, ‘gee-zus,’ as opposed to the correct Spanish pronunciation, ‘hay-soos.’) –– Justin Hobart, A Long Way to Go

Stacey Cole, superintendent of Storm Lake Community Schools (left), Chief Chris Cole, Storm Lake Police (right)

The class’ interviews exposed wide-ranging, often polarized perspectives. Nathaniel Hieber ’21, the lone graduate student on the project, sought to find the town’s true narrative by finding a common thread throughout interviews.

“Depending on the race or age of the person, how long they've been in Storm Lake, and whether they'd be born there or just moved there, we got different interpretations of what the town was like,” Hieber said.

Most of those interpretations came from ideas around racism, equity, and the treatment of workers at the town’s meatpacking plant, which has been the center of controversial pay and safety concerns for years. Hieber said after talking with public relations officials from the plant, the class was able to get a viewpoint opposite public opinion and piece together the complicated relationship between the plant and local families. Some workers have been able to build sustainable careers and support their families, but others struggled with low pay and long hours, and, in a few cases, circumstances that families say led to their deaths.

The stories that change our world

Inspiring. Gut-wrenching. Unbelievable. The stories uncovered by Offenburger’s students tell the tales of migrant families searching for the promise of a better life in America and settling into a unique bubble in the midwest. For some, it’s an American Dream realized, but for others, it’s a broken promise hidden behind the facade of progress.

Abel Saengchanpheng, born in a Thai refugee camp, arrived in Storm Lake in 1997 and joined the meatpacking plant after high school. He’s now in charge of 300 workers as a general foreman and lives a comfortable, upper-middle-class life.

On the other hand, advocates Steve and Willis Hamilton, share the stories of the hundreds, if not thousands, of plant workers they represented in legal battles, including the family of a worker who recently died of COVID-19.

There’s also Marroquín, the Storm Lake college student grappling with the racial and economic politics of Storm Lake as he transitions into adulthood.

These stories, and more, are cataloged in the final project, “Small Town, Big World,” which mirrors the oral history format used by the nonprofit StoryCorps. Miami students partnered with journalism students at Buena Vista University to gather personal narratives and create written and multimedia profiles on residents connected to Storm Lake High School. Together, both classes listened to understand how Storm Lake newcomers are more than immigrants but also people with stories of determination and sacrifice.

A 2004 Storm Lake Times article discover by Miami students. The article profiles an El Salvadoran woman.

Beyond history, Offenburger’s course teaches students to interact with civility, empathy, and curiosity, and develop content-specific knowledge for real-world projects that will impact a multicultural society. Unique skills like interviewing and historical transcription, capturing authentic narratives, and relating to contradictory worldviews are techniques that benefit students in his course who study a range of interests.

LeRoux points to the course as unique to her Miami experience. While she appreciated her time as an English major, studying literature and delving into context, she yearned for something concrete.

“I felt like I should finish off my time here at Miami doing something that actually meant something or would have some sort of impact,” she said. “This class was a way for me to feel like all of my four years were coming together.”

Along with “Small Town, Big World,” the class’ historical research will help shape narratives for an upcoming documentary on Storm Lake, produced by Los Angeles-based production company Anchor Films, and the entirety of the course research portfolio and materials will be donated to the Buena Vista County Historical Society. The Storm Lake Community School District plans to promote a number of Miami student profile pieces in neighboring newspapers. Additionally, the Storm Lake Times will publish multiple student writings over the coming weeks.

If you'd like to see the articles by this class as they are published this summer, please subscribe to the class blog. Copies of all writings will be posted online.