Race, Sexuality, and Lived Experiences Take Center Stage for New EHS Professor

James M. Loy, Miami University

As education continues to evolve in light of the vast cultural changes that now sweep across most of society, some colleges of education are pursuing avenues of study that are more relevant to the lives of increasingly diverse student populations.

For the department of educational leadership (EDL) in Miami University’s College of Education, Health and Society (EHS), this is leading to a growing focus on critical youth studies, which examines the dynamic cultural contexts present in the lives of young people.

“EDL was one of the first departments in an educational school to be consciously doing cultural studies,” says Kathleen Knight Abowitz, EDL department chair. “There is a long tradition of critical thought about schooling and also looking at education as more than schooling. And that’s where the critical youth studies sequence fits in.”

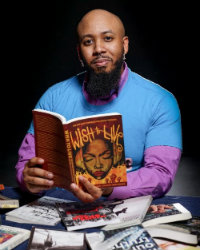

A leading contributor to this movement is Dr. Durell M. Callier, a new EHS assistant professor of educational leadership, who calls his work “deeply personal, politically spiritual, intrinsically accountable, and ultimately artistic.”

For Callier, issues of race, gender, sexuality, love, violence, and belonging all take center stage as he weaves together personal narratives, performance studies, and academic inquiry in several unique ways.

“Durell takes knowledge about the lives of youth, particularly youth that end up invisible to other people, and he creates performances that can narrate that knowledge,” Knight Abowitz says. “So part of the performance piece is trying to create public forums for dispensing knowledge that’s sort of invisible or hidden. And a lot of that work is not just centered on school. Critical youth studies remind us that kids are whole people. They have agency and they live a lot of their lives outside of these institutions called schools.”

What follows is an excerpt from a conversation with Callier about how he approaches critical youth studies, his role as an artist-scholar, Black Lives Matter, and more.

What do you hope students will take away from your classes?

Callier: When they leave my class, I want students to think critically, to think creatively, and to value difference. What we know as people who study education is that we have had a series of policy created that focuses more on testing than it does on learning. It is more about the right answer than the exploration of a topic, and that there is only one right answer rather than a great big world of possibility. And I have the awesome and daunting responsibility and challenge of undoing that work. That is what I mean by thinking critically. It is getting students to dig deeper, to actually explore their interests and the world around them, and to provide that opportunity, which oftentimes up until my class many students haven’t had.

What perspectives do you want them to take into the world?

I want them to understand that who they are and where they come from has something to say about what we learn in class, and that what we learn in class has something to say about where people come from and the lives they currently live.

I want them to understand that who they are and where they come from has something to say about what we learn in class, and that what we learn in class has something to say about where people come from and the lives they currently live.

And that provides interesting dilemmas in the classroom because many students don’t know what to do when asked to center themselves and to think creatively. Even my graduating seniors, who have experience, are used to being told what to do. And when given the option of what they could do, they don’t know what to do with that. So I try and open up a buffet of possibility, and that becomes really daunting if you’ve only ever been given the same meal every day.

You mentioned valuing difference also being important. How does that fit into your class?

The course I am thinking primarily about is the critical youth studies course, which is EDL 203. The “critical” in critical youth studies asks us to think about identity and to not construct youth— as a youth studies framework typically did— as white middleclass able bodied (mostly male) folks with all these sorts of privileged identities. So how do we think of youth as having various cultures and subcultures that impact society? How do we think of youth as autonomous individuals?

You have called yourself an “artist-scholar.” Do you still consider yourself to be an artist-scholar and what does that mean?

Yes, I do still think of myself as an artist-scholar. I do think it is challenging for a lot of different reasons, some of which are very structural.

I came to integrate performance into my work after taking a theatre course called “Devising Social Issues Theatre” at the University of Illinois. It was in this class I was taking alongside my other research methods classes when a light bulb went off. What my professor—Lisa Fay of Lisa Fay and Jeff Glassman Duo—was asking me to do was research, but it was not called “research” in the same ways my methods classes talked about research.

Sometimes the two terms “artist” and “scholar” seem as if they are antithetical to one another. But they don’t have to be. Because the questions that artists ask of society are the questions that researchers are asking. They draw upon, at times, different but similar ways of knowing. I think the biggest difference is the value output. So for scholars the value output is all written products. And for an artist—and there are multiple types of artists—those products can be more ephemeral and they don’t necessarily get disseminated in a journal.

So it can be about using art or performance to reach certain audiences that may not read an academic journal?

Yes. It can disseminate knowledge in a way that taps into lived experience and to reach an audience in a way that what’s written on paper sometimes wouldn’t reach. And if the people you are trying to reach are people who don’t have access to academic journal subscriptions, but who might be able to come out to a performance, or who won’t read a certain type of report but who might read a poem, then how do you reach multiple audiences, I think, is what these other ways of knowing ask specifically.

And the term artist-scholar is also about how communities are engaged. For instance, you can be somebody who works in higher education, who’s work impacts communities, but who also might not have a relationship to the community in which that university is located, or the community that you are even studying.

So I think artist-scholars ask for a type of community accountability and that can, at times, be antithetical to what is privileged in academia. Even though our mission statements often say something related to engaging local and global communities, the work this entails—creating sustaining relationships and partnerships and being in community —are processes that are undervalued in an academic market, which emphasizes a variety of “measurable outputs” over people.

What are some projects that you’ve been working on?

One of the projects, I am working on connects the premature deaths of Black youth to the ways we have historically conferred or denied value in systematically learned and culturally supported ways to Black people in the U.S. Filling in the gaps of our cultural memory, this work archives the complexities of experiences often left out an analyses of issues surrounding the deaths of Black folks in particular, and Black youth specifically. These stories often flatly associate premature death with gang violence, for instance, or random acts of violence, rather than to think about them in any type of systemic or historic way that also would help us understand what people could do at multiple social levels to intervene.

Photo Credit: twobrainz

I am currently revising an article that connects three acts of violence that all happened in Baltimore, and that take place outside of schools. I am looking specifically at the death of Korryn Gaines, Freddie Gray and Mya Hall, a transgender woman. And I am asking the question, “What about our society, our culture, makes these types of deaths acceptable and not necessarily extraordinary?” Society almost seems to take it for granted that they happened.

So what are the types of messages that we are sending out as a society, as a culture, that almost necessitates in some ways these premature deaths? And in this moment, it is interesting that many times people see Black Lives Matter as a declaration. But it is also a question as to which black lives matter? When? And for whom? So I am not only exploring that declaration, but also that question in many ways. That is to say, what is it that we are learning as a society about how to value or not value particular lives, people and communities? This is the significance of thinking about education beyond schooling. To locate those sites of learning and knowledge production which are infused into our everyday lives and practices. And to examine the consequences of taken-for-granted social practices, practices which are an ever-present site of learning.

From your perspective, how does cultural studies and performance studies fit into educational leadership?

The field of educational leadership is an interesting space. It is where you will find policy folks and curriculum folks and people who are interested in education at multiple levels. So there is space to think about education as not just primarily located at the site of schooling. But what are the multiple things in our society that impact young people, learning, and how our schools function and how can we illustrate these impacts?

Cultural studies and performance studies as fields provide frames to understand, and interrogate experience—attuning to the ways issues of race, gender, sexuality, class, and other forms of social categories and structures impact our everyday lives and foster inequities and marginalization within our society. Equally so, cultural studies and performance studies can seek to deconstruct the very structures which foster inequity within our society. Deconstruction can look like imagining and enacting new ways of being in the world. New ways beyond our current structures of inequity and marginalization. That’s where it fits in.