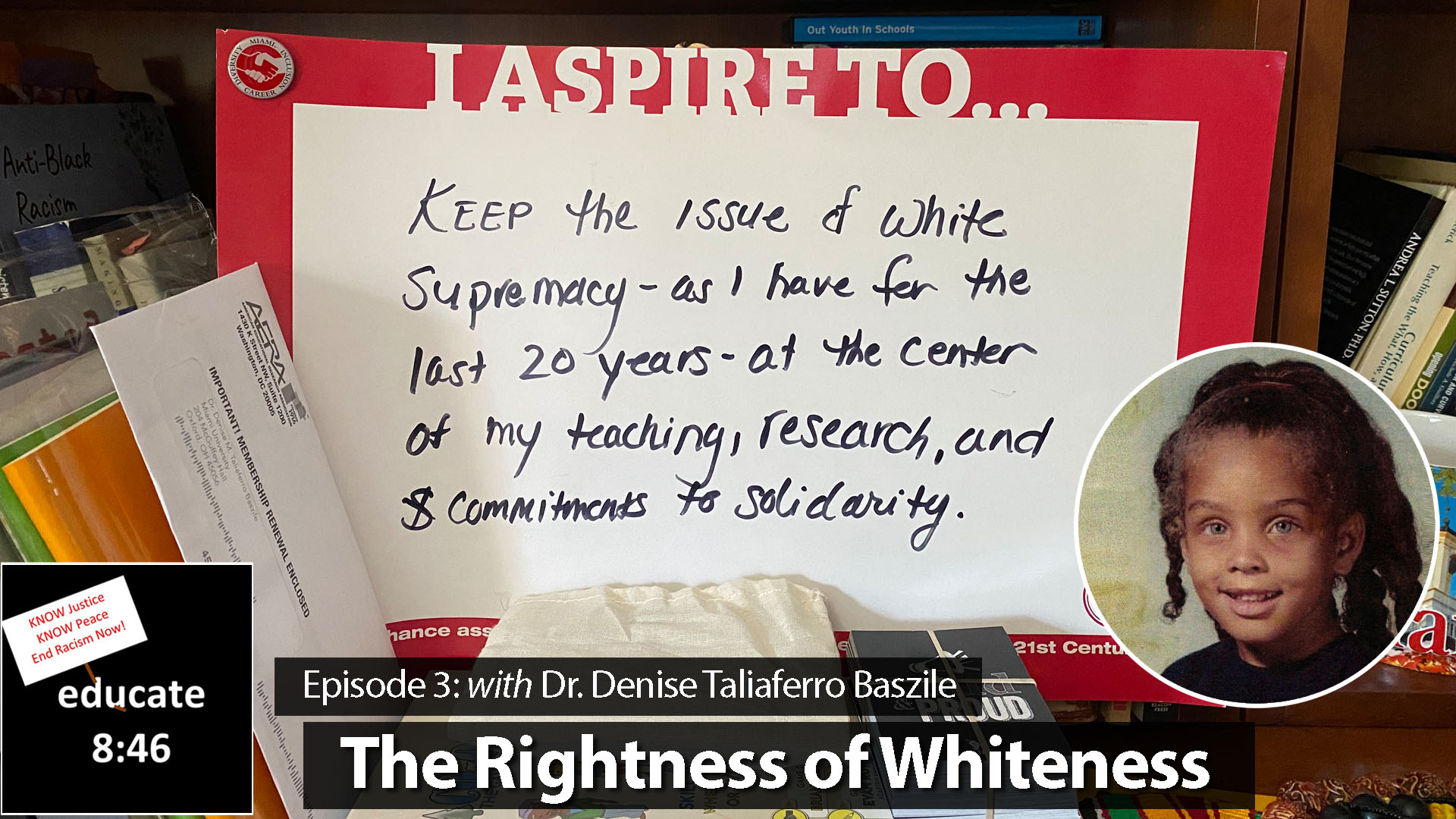

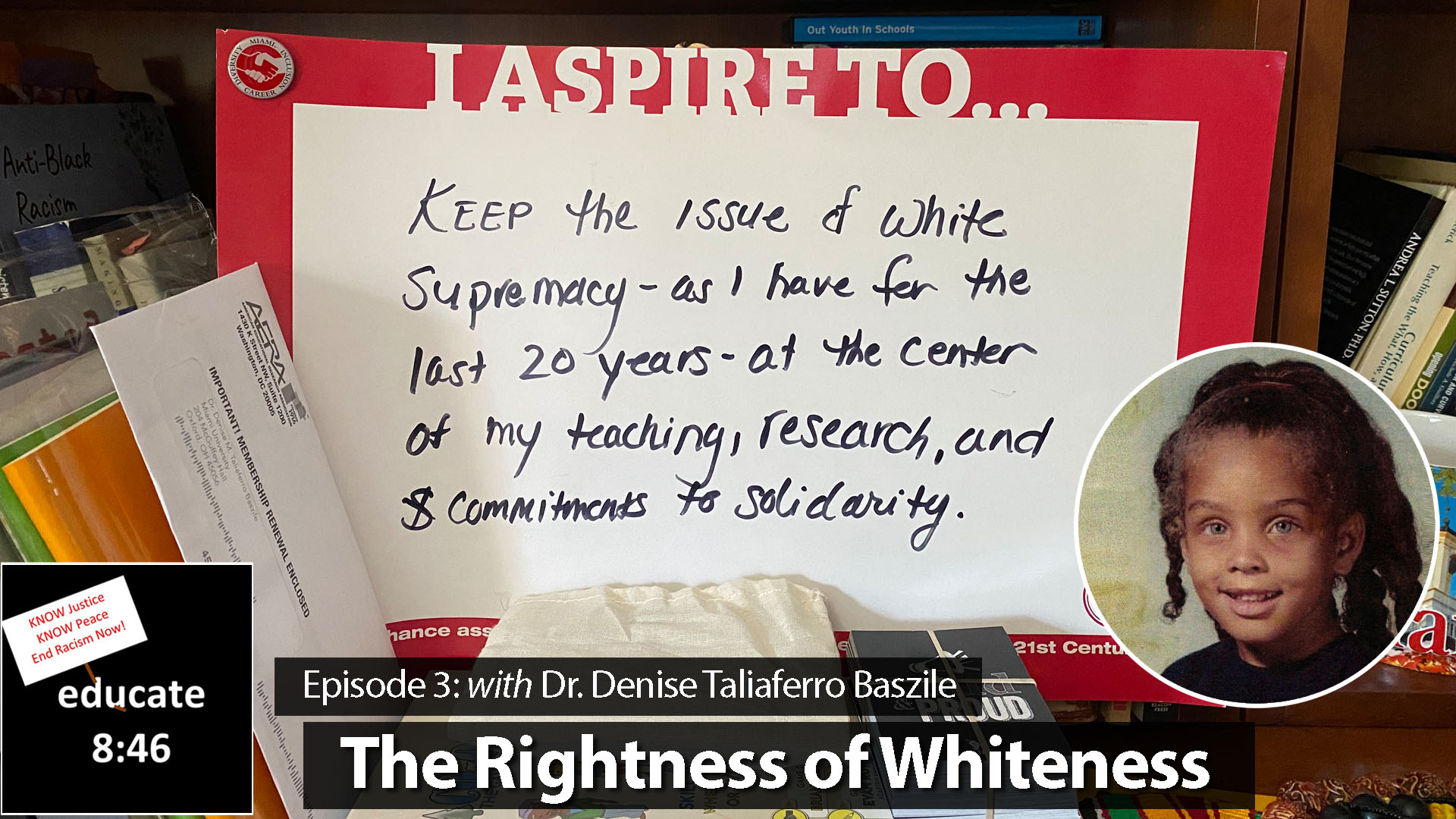

Educate 8:46 Episode 3

The Rightness of Whiteness

More Miami Podcasts Request Information

Historically, much of everyday life in the U.S. has been organized around the idea that white is good, pure, righteous, and most deserving of privilege, power, and protection. In this way, white supremacy no longer derives its power from an explicit social acceptableness. Instead, it has wedded itself, almost imperceptibly, to that which is considered neutral, normal, safe, and reasonable.

Additional Resources:

PBS, The History of White People in America

Read the transcript

[Music]

Denise Taliaferro Baszile:

Hey, hey good people. I'm Denise Taliaferro Baszile, and this is Educate 8:46.

8 minutes and 46 seconds is the amount of time that officer Derrick Chauvin had his knee on the neck of George Floyd, draining the life from his body. So the premise of Educate 8:46 is simple -- what can we teach and learn that can support the struggle against white supremacy and anti-blackness, and all inter-systemic injustices in 8 minutes and 46 seconds?

[Music]

Today on Educate 8:46, I want to open with a couple of questions for you. Can you remember the first time you registered racial difference? Can you remember what you thought and how you felt? If we stop and ponder, we can all call up such a moment because in our society having no race is like having no gender. And although both race and gender hierarchies are ideas we have made up to describe our realities, often in limiting and troubling ways, we nevertheless use them every day, all the time, to determine how we think about people, and ultimately how we behave toward them.

Now, honestly, we don't have to explicitly or intentionally teach our children how to think about themselves, or how to think about different groups of people. They learn it quite easily in a number of ways. From television, billboards, textbooks, fairy tales, and all kinds of people including teachers, friends, family members, and parents, who don't even realize that they are passing on racial and, sometimes, racist ideas to their children. Historically, in the U.S. much of our everyday living has been organized around the rightness of whiteness - the idea that white is good, pure, righteous, most deserving of privilege, power, and protection. Again, no one has to say that out loud. We can just get that idea by reading the most popular fairy tales, learning about important historical figures in school, reading great works of American literature, memorizing American presidents, watching tv, pondering white Jesus, or just becoming aware of our neighborhood - who lives in it and who doesn't, or what it looks like compared to the one across town.

My first time registering racial difference was in the first grade, but I have to begin the story in the summer before I started kindergarten, when my parents brought a little house on the northwest side of Detroit from a white family. It was 1971, and we were moving from a two-family flat in another part of the city to this single-family home in a “good” school district. I started kindergarten at an elementary school that fall. I was excited to have lots of new friends in a very inviting classroom decked out with all kinds of toys. This is where I met Jimmy. I had the biggest crush on Jimmy. He was a little white boy who paid little to no attention to me at all, and I was sure this had everything to do with the fact that I was a girl. Anyway, all that year I sat next to Jimmy. I smiled at Jimmy and I tried to convince him to play with me to no avail.

So we ended the year, went into the summer, and when I returned for first grade, I was looking everywhere for jimmy. But he was gone, and so were most of the other white kids in my class. I remember thinking, “Who stole all the white kids?”

I could see that most of the white people, who lived around us, were moving away. But I didn't understand why until sometime later I overheard a conversation between adults, who were insinuating that black people were ruining the neighborhood. That was the first time I realized that we were the reason they were moving away. Much later in my life, I would come to learn about the pervasive practice of redlining and white flight that absolutely segregated the city and its surrounding suburbs - as most white folks, at least those who could, moved further and further out of the city over the years to avoid what they believed to be the inherent liability of black people. That wherever we happen to live, our presence alone would drag down the quality of the neighborhood, and the value of their homes.

Did these white folks think of themselves as racist? Probably not. Just hard-working families who wanted to live in good safe neighborhoods, where they would preserve their property values. And I assure you, just like the white folks moving out, the working class and lower middle class black folks moving in wanted the same thing – good, safe neighborhoods where they could reap the benefits of home ownership.

The problem with all this, however, is that good, safe, and strong property values were all code for whiteness, for protecting the privileges and the power of whiteness. And the overwhelming insinuation that lingered in the back of my six-year-old mind was the absolute association of blackness with bad, unsafe, and the thing that was dirtying up the neighborhood. Perhaps in my next series we can actually chat about what happens in Detroit over the next decades, how this fabricated narrative of blackness bares rotten fruit, and generates profound racial injustice and inequity.

But for now, the crux of today's lesson is to recognize that white supremacy works not only at the deepest levels of our individual subconscious minds, but also at the deepest level of our society substructure. So even if the only people who actually professed a resounding and explicit belief in the superiority of white people were some white men of the 17th and 18th century, the truth is is that we are still, right now, today strung up by the fact that they baked this idea into our systems, institutions, laws, practices, and, in many cases, our hearts and minds. In this way, we find ourselves in a vicious cycle, where our beliefs and consequential actions work to uphold racial systems and institutions, and those same systems and institutions discipline our beliefs and our behavior.

This makes white supremacy as American as apple pie, and not so easily contained, disregarded, or undone. This is why I refer to it as a logic, and, more specifically, even as a pathologic. Because it's not simply a belief negotiated by individuals, but a logic by which our society is fundamentally organized. White supremacy no longer derives its power from an explicit social acceptableness. Instead, its power lies in the ways in which it has simply wedded itself, almost imperceptibly, to that which is considered neutral, normal, safe, and reasonable. So much so, that even when we dispel our laws of racist language and ideas, we so often still manage to leverage them in racist ways. In ways that, again, protect and value whiteness, and disparage, to different degrees and in different ways, all others.

White supremacy in this discourse of race is not a simple flaw in our otherwise great democracy. Unfortunately, it's the normal state of affairs -- unless, and until, we actively, consciously, and with great conviction learn otherwise. If you're interested in heading in this direction, a good place to start is by checking out the new PBS animated musical series The History of White People in America.

Now having said all of this, we should be very cautious of associating white supremacy only with white people. As an organizing logic it, shapes how we all think about ourselves, and about each other. So in the next episode, I will highlight how different groups of people have wrestled with the adverse impact of white supremacy on their habits of mind, behaviors, and life circumstances. I especially want to talk about this in the way that I know best - how the idea of white supremacy has consistently ravaged black lives for centuries on end, not only through the trafficking of black bodies in the slave trade, but more insidiously, more grossly, through its absolute production of a coinciding and unrelenting anti-black logic.

[Music]

Until next time, thank you for listening to Educate 8:46 in the name of George Floyd and all others whose lives have been unjustly ended by the power of white supremacy.