Miami University marks the 50th anniversary of local Freedom Summer history

Written by Margo Kissell, university news and communications, kisselm@miamioh.edu

Photographer Herbert Randall no longer has the nightmares that haunted his sleep after a harrowing incident while documenting the 1964 civil rights initiative known as Freedom Summer.

Fifty years later, Richard Momeyer believes there is still much to learn from the hundreds of volunteers — many of them white college students — who trained in Oxford before heading south to register black voters and set up freedom schools and community centers.

An estimated 800 volunteers went through orientation training June 14-27 of that year at the Western College for Women, which is now part of Miami University's Western campus.

Three civil rights activists — Michael Schwerner, 24, James Chaney, 21, and Andrew Goodman, 20 — were murdered in Mississippi soon after leaving Oxford. Their deaths stunned the nation and sparked a major federal investigation. It was code-named "MIBURN" for Mississippi Burning after their charred station wagon was found on June 23.

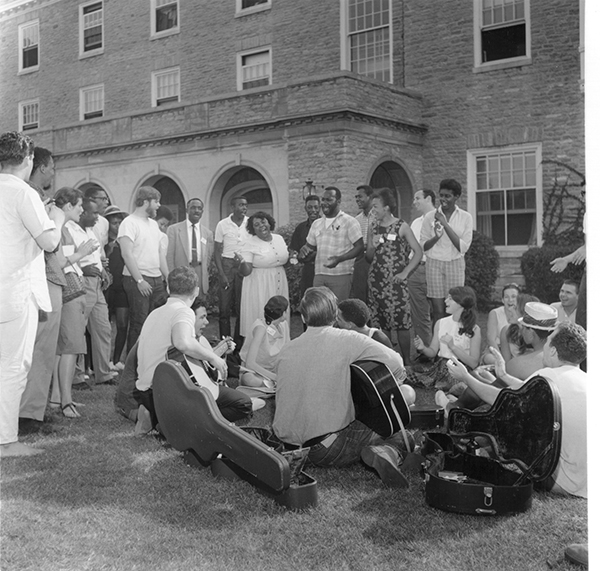

Freedom Summer organizer Bob Moses talks to volunteers at an orientation in Peabody Hall, Western College for Women, now part of Miami's Western campus (photo Ted Polumbaum, Newseum Collection).

As the university and nation mark the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, Momeyer — professor emeritus of philosophy at Miami who participated in the training sessions one week after graduating from college — said the pivotal civil rights campaign is a good reminder of how important "the idealism, energy and commitment of young people are to make social change."

Myka Lipscomb, a Miami junior majoring in theatre, has immersed herself in Oxford's Freedom Summer history and is now helping to share that story.

The 23-year-old Middletown woman is one of several student tour guides on the "Walk with Me" interactive walking tour who take visitors into Peabody and Clawson halls where that training took place.

They take on the personas of Freedom Summer staff members and trainees during the tour, revealing their inner thoughts as recorded in letters and diaries. At the nearby Freedom Summer Memorial, they honor those who lost their lives.

Lipscomb said she gets chills every time she recites the words of a female student at orientation training who was conflicted about going to Mississippi because she was afraid to die. That student was younger than Lipscomb is now.

"I love those moments when we really make sure they know these were people your age," Lipscomb said about leading tours for her peers.

"Different kinds of horror"

Randall, now 77, returned to Oxford this spring at the request of a professor and students in the media, journalism and film department working on a documentary film project about Freedom Summer.

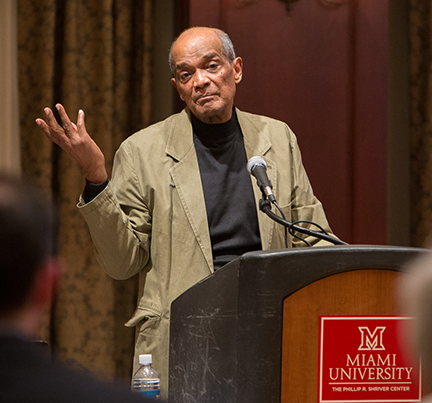

Photographer Herbert Randall spoke at Miami in March about his experiences documenting the work of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers and volunteers in Oxford and in Mississippi during Freedom Summer. His photos will be exhibited at the Miami University Art Museum Sept. 2-Dec. 6 (photo by Scott Kissell).

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a lead organizer of the Mississippi Summer Project (as the initiative was known back then) had hired him to record the work of SNCC workers and volunteers.

Randall recalled how the second week of training was overshadowed by the June 21 disappearance of Schwerner and Goodman, white New Yorkers, and Chaney, a black activist from Mississippi. All three Congress of Racial Equality field workers disappeared while investigating a fire at a church that had been torched by the Ku Klux Klan.

Randall donated 1,800 negatives in 1999 to the archives of the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, the largest Freedom Summer site where he had spent his time.

He regrets that for security reasons he wasn't able to photograph the local people, including those who housed him and other volunteers while in Mississippi.

"I really can't express how important local black Mississippians were," he said. "They fed us, they housed us (and) they protected us."

The audience who gathered at Miami's Shriver Center in March to hear Randall speak hung on every word as he told of the night his integrated car was followed.

A volunteer sitting in the back seat spotted the trailing car as they approached the house where Randall was staying so they drove around the block a couple of times.

As they rounded the corner a third time Randall, who was sitting up front, told the driver to slow down enough so he could jump out of the car. It could then drive on without brake lights revealing their plan.

Randall slipped in the back door of the house. When he reached the front room, he saw the homeowner with his left hand on the screen door and a shotgun in his right.

"I said 'Mr. Wilson' as loud as I could without waking the family. 'Please don't go outside.'

'He said very loudly, 'Herbert, are they bothering you?' "

Randall told him nobody was bothering him and said, "Please don't go outside." Mr. Wilson didn't go outside, but the incident gave Randall nightmares for years.

"The nightmare would always start the same — Mr. Wilson going out that door, then the scenario would change to different kinds of horror."

Freedom Summer workers and volunteers gather to sing outside of Clawson Hall (photo by George R. Hoxie; courtesy of Smith Library of Regional History).

Bringing history to life for new generations

Hearing Randall tell what he remembered from that time made Freedom Summer real for Emily Potten, one of 17 Miami students who took clinical professor Kathy Conkwright's "Documenting Freedom Summer" classes.

The students made mini documentary films of various subjects that will be worked into the larger documentary Conkwright is producing and hopes to complete later this year.

Potten and classmate Sarah Hornbeck chose Randall as a film subject after Hornbeck discovered his book, Faces of Freedom Summer: The Photographs of Herbert Randall (University of Alabama Press, 2001).

"The stories he told were so in-depth and incredible," said Potten, who graduated in May.

Conkwright said she hopes the experience made her students realize they aren't so different from the Freedom Summer volunteers 50 years ago.

"I wanted them to realize they have the power to make change," she said, "and also that they have a voice."

A chance to back out

The ink was barely dry on Momeyer's philosophy degree from Allegheny College when the 22-year-old Pennsylvania native arrived in Oxford to assist with training in nonviolent resistance.

He played the victim in simulated attacks to show other volunteers how to protect themselves, as he had done during his own civil rights activism in Nashville and elsewhere during the previous two years.

In a chapter he wrote in Finding Freedom: Memorializing the Voices of Freedom Summer (Miami University Press, 2013), Momeyer shared that he had experienced assaults with "scalding water, bricks, fists and clubs" and was repeatedly jailed.

On June 27 — the last day of training and four days after the burned-out station wagon was found — Momeyer recalled SNCC leader Bob Moses telling the volunteers that Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman were presumed dead. If any volunteers didn't want to travel south, this was their chance to back out and that there was no shame in that, he said.

Volunteers practice non-violent resistance during Freedom Summer training at Western College for Women (photo by Ted Polumbaum, Newseum Collection).

"The next day people got on buses and in cars and headed to Mississippi," Momeyer recounted.

An impetus for national change

Momeyer, who went to Georgia, said the public outrage over what happened to the three activists galvanized the nation and undoubtedly helped pass the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Congress passed it July 2. On Aug. 4, the bodies of Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney were found in an earthen dam on a local farm near Philadelphia, Miss., not far from the burned-out church.

The state of Mississippi made no arrests but the U.S. Justice Department indicted more than a dozen suspects for violating the men's civil rights — the only way the federal government was able to get jurisdiction in the case.

Seven of the 18 defendants, including a deputy sheriff, were found guilty but none on murder charges, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

On June 21, 2005, white supremacist and part-time Baptist minister Edgar Ray Killen, 80, was convicted of three counts of manslaughter and sentenced to 60 years in prison.

Marking the 50th anniversary

Momeyer, who has lived in Oxford nearly 45 years, said he's proud Miami — which acquired Western College for Women in 1974 — has taken ownership of this important civil rights history and is marking the 50th anniversary in several ways.

Ann Elizabeth Armstrong, associate professor of theatre who created the walking tour in 2004 for the 40th anniversary, is still involved in coming up with new ways to share the story of Freedom Summer with new audiences.

Myka Lipscomb, junior theatre major (left), and Dayday Robinson, graduate student in theatre, reflect at the Freedom Summer Memorial on Miami's Western campus. They are guides for the "Walk with Me" Freedom Summer interactive walking tour (photo by Margo Kissell).

She has been awarded a nearly $60,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to develop a prototype for a location-based app and Web-based game for her project, "Orientation to the Mississippi Summer Project: An Interactive Quest for Social Justice."

Her capstone class this spring wrote a historical play about Freedom Summer to be performed by young docents at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

On a recent walking tour as Lipscomb and fellow guide Dayday Robinson escorted visitors from Peabody Hall to the memorial, the two women sang "Freedom is a Constant Struggle," a freedom song like those sung during the orientation training to empower the volunteers and deepen their commitment to the movement.

Robinson, a graduate student in theatre, finds personal fulfillment in performing this Freedom Summer role for those interested in learning the history so it isn't forgotten.

"I love the idea we are going to spread the word," she said, "and through them, the word of mouth continues."

Miami is hosting a series of events marking the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, including a commemoration June 20. Read more here.