Miami's herbarium home to about 650,000 dried plants - and no beetles

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

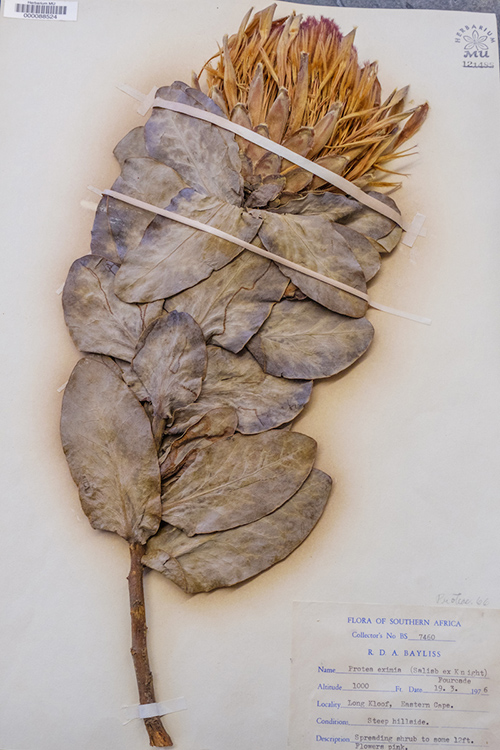

A South African plant

Mike Vincent is in search of coffee — but not the kind to fill his cup.

He’s on the hunt for a dried plant from the genus Coffea arabica.

The curator of the Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium in Upham Hall winds his way through the tall metal cabinets spread across three floors known as the stacks. He walks down a row and opens a cabinet, revealing neatly stacked sheets of paper containing preserved coffee plants.

He pulls out one that was once part of a doctoral student’s botanical study in South America.

“This was being grown in a family’s garden in a village in Peru,” said Vincent (Miami ’78, MA ’83, Ph.D. ’91), an instructor of biology who has been the curator for 30 years.

The herbarium is a systematically arranged collection of approximately 650,000 dried plants from around the world. The collection dates back to the 1790s and burgeoned in 1967 with the purchase of Oberlin College’s sizable collection.

Mike Vincent in the herbarium stacks. View the video below to see the smallest flowering plant in the world.

Still believed to be Ohio’s largest herbarium, the collection has a variety of specimens, including vascular plants as well as bryophytes, fungi, lichens, algae and fossil plants.

“We have all sorts of things. Basically anything you can think of, we probably have representations of it,” he said.

After working here so many years, Vincent jokes that he has the research facility mapped out in his head, which means he can find things quickly such as black pepper, orchids and clovers.

His “lifelong study of clovers” got its start by accident.

Vincent said he began working on the classification of the genus Trifolium in the late 1980s during a field trip to south central Ohio. It was raining, the clay soil was slippery and Vincent slid down a hill.

“When I stopped sliding, I sat up and I was in this patch of pink stuff that I had never seen before. It turned out to be a native species of clover that was considered extinct in Ohio at the time,” he said.

Vincent wrote a paper on the rediscovery of that species in Ohio, and his research on different varieties of clover continues today. As a systematist (a biologist who specializes in the classification of organisms), he is responsible for going through acquired collections. One recently acquired moss collection arrived in 100 boxes. He has whittled that down to about 20 after going through each one to decide what was worth keeping.

Those items join other specimens, including a batch of mosses from the government’s U.S. Exploring Expedition of the Pacific Ocean in the early 1800s that played an important role in the growth of science in this country.

Searching online through external portals

Thanks to advances in modern technology, researchers from around the world can now study images of about 200,000 of the herbarium specimens now available online through external portals. Among them is a collection that once belonged to Caroline Bingham, a botanist who collected algae in California in the 1800s and became one of the first women to publish scientific papers on botany.

The portals are a convenient way for scientists to do research. The herbarium also participates in an international exchange program.

Kate Chapel; below, Chapel collects plants during a collecting trip in the Bahamas.

“People doing climate study are looking at herbarium specimens to see how plants may have changed because of climate changes,” he said. “People looking at the distributions of rare or invasive species will look at records in herbaria to see how their distributions have changed through time.”

Miami undergraduate and graduate students also have done research through the herbarium.

Kate Chapel (Miami ’14), who majored in botany and worked at the herbarium, conducted research with Vincent on an undescribed species of North American clover. She did a lot of measurements and statistical analyses “and was able to show pretty clearly that it was distinct from the other species," he said. Chapel and Vincent co-published in 2013 a new species name, Trifolium kentuckiense, the holotype. Vincent likes how they are able to give students a chance to do research and publish papers.

“Not only is it a great way to learn, but then it really starts them out on their career path,” he said. “It’s very important, especially for someone in the sciences, to get that kind of training so they can get a good start.”

Chapel agreed.

Chapel agreed.

“Gaining research experience and a publication was, I believe, crucial to me getting into graduate school. I now have a master's in conservation ecology with a focus on terrestrial ecosystems from the University of Michigan,” she said.

Chapel said working and doing research in the herbarium taught her data collection skills, how to work with specimens properly and how to work with a faculty member.

“In addition to my work with Dr. V on the Trifolium, I was able to do research with him in the Bahamas (Turks and Caicos). We went on a collecting trip, and I was able to study the specimens once we got back to the states with funding from the University Summer Scholars program,” said Chapel, a botanist at Lake Erie Metropark who is exploring potential doctoral programs.

Preserving plant specimens

Back at the herbarium, Vincent and his students work in the front prep room to prepare specimens for the collection.

Items are first dried in a plant press, then labeled and mounted on large sheets of paper.

A specimen of Trifolium kentuckiense, the species named by Vincent and Chapel.

And while most of the plant specimens are stuck on the paper with glue or tape, others are attached in a truly unique way — with thread. Those are in a large part of the herbarium’s European collection that was collected by one woman during the Victorian era.

Everything that comes into the research facility must pass through a freezing cabinet cooled with liquid nitrogen. It is set at 80 degrees below zero centigrade to kill any insects and eggs.

Mothballs are added as an extra safeguard in the stacks.

“We keep them in the cabinets because these are very tasty to beetles especially, and silverfish, that would come in and eat at the collection,” he said.

And if you’re wondering, Vincent pronounces the “h” on herbarium, but said it’s fine to keep it silent. It depends on your preference.