Miami's academic boot camp drives up student-athlete GPAs

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

The days start out tough and grow more difficult.

There’s plenty of grumbling among the incoming student-athletes, who didn’t expect it to be so taxing.

But after six weeks, they’re ready — for the classroom, just as they are for their first collegiate game.

But after six weeks, they’re ready — for the classroom, just as they are for their first collegiate game.

Welcome to Miami University athletics’ academic boot camp.

The RedHawks Summer Bridge Program, as it’s formally known, started seven summers ago as a way to prepare first-year athletes in select sports for Miami’s rigorous academic experience.

This summer, 30 first-year student-athletes — football players plus men’s and women’s basketball players — are in the program that ends Aug. 4.

All are required to attend, even if they earned a 4.0 GPA in high school.

The reason football and basketball players participate is because the revenue generated by those teams allows Miami athletics’ budget to accommodate the NCAA’s rule that first-year athletes starting in the summer take six credit hours, said Craig Bennett, assistant athletic director for academic support services. Bennett developed the program with Rodney Coates, professor of global and intercultural studies.

Miami football coach Chuck Martin has become the program’s biggest believer.

“Our Summer Bridge Program is by far the best at preparing students for the transition from high school to college that I have been associated with in 25 years,” he said.

That transition can be overwhelming for student-athletes, who may practice 20 hours a week, have team meetings and travel to and from games in addition to coursework.

Statistics point to success

The student-athletes who took part in the 2016 Summer Bridge Program posted a mean grade-point average of 3.39 last fall semester, the highest GPA yet for the first-year athletes.

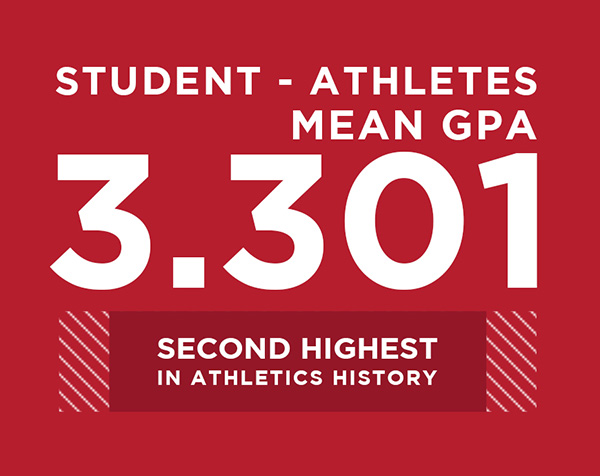

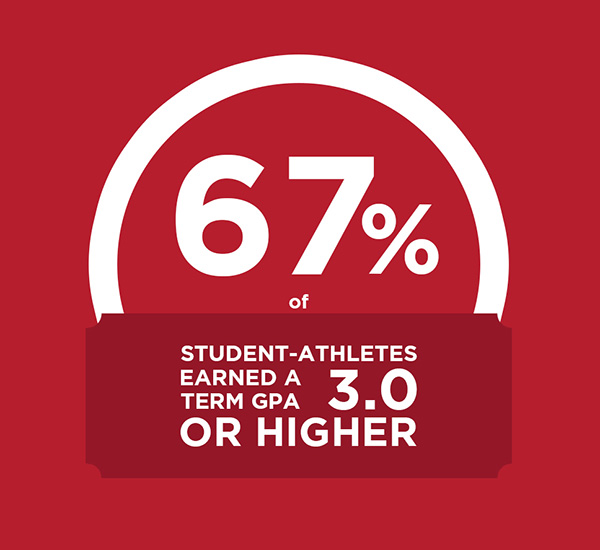

Organizers believe the program’s success is a big reason why Miami’s 525 student-athletes collectively posted a 3.301 GPA in spring semester, the second highest GPA for a semester in Miami athletics history. (The highest was 3.313 in spring 2015.)

While 17 of 19 teams achieved team GPAs of 3.0 or higher, only football and men’s basketball didn’t. But Bennett noted both teams posted their highest GPAs this spring.

“We haven’t had one football player or basketball player go into the summer ineligible,” said Bennett (Miami MS ’00), who speaks at conferences about the program. “When I say that at MAC (Mid-American Conference) meetings, people fall out of their chairs.”

Bennett, who started at Miami in 2007 as athletic academic coordinator/learning specialist, teaches the skills development class. He covers such things as time management and learning to properly use online research tools.

The Summer Bridge Program also features a writing course and, for some athletes, a women’s studies course and a one credit hour class in which they plan summer activities for Oxford youth. It counts as experiential learning credit toward their degree.

“I want athletes to become acclimated to Oxford as a community and see themselves as engaged and valuable members of the community,” said Ann Fuehrer, associate professor of global and intercultural studies (women’s, gender, and sexuality studies) who teaches two classes.

And then there is the course that student-athletes consider to be the toughest because of the amount of work — Coates’ four credit hour introduction to black world studies that meets for two hours, four days a week.

Coates wants the 20 football players taking his class to see themselves as more than athletes.

“I want them to see themselves as scholars,” he said. “I want them to see, just like over there (at the sports complex), their efforts will translate.”

Rodney Coates, professor of global and intercultural studies, said he wants his class of 20 football players to see themselves as scholars. (Photo by Jeff Sabo)

“What’s your game plan?”

Coates has them reading an average of 35-40 pages per night and writing three- to five-page essays, submitting critical discussion questions, doing research and then writing an abstract from their research. Their midterm is a 15-page report.

And that’s with no academic support because Coates wants them to see what they can accomplish on their own. They don’t realize they’re learning how to study and think critically, analyze and do research, as well as ask questions and participate in class.

During the summer, student-athletes are assessed for reading, writing and learning skills to determine if additional academic support is needed to succeed in the fall and spring semesters. Bennett said part-time intervention learning specialists work with some students to “keep them on track, organized and continuing the tools that we taught.”

On Day 1, Coates gets their attention by asking what percentage of college football players make it to the NFL. Most know the answer: 1-2 percent, he said. Those NFL players play an average of three to four years and a high percentage of them wind up bankrupt.

“I say 99 percent of you guys are not going to make it to the NFL. What’s your game plan? You need another option. This is your other option.”

On Day 2, Coach Martin, who has sat in on the class in the past, drops by Upham Hall and tells his players that he backs the program 100 percent.

On Day 2, Coach Martin, who has sat in on the class in the past, drops by Upham Hall and tells his players that he backs the program 100 percent.

“Dr. Coates’ class gives them so much work that whether they were a valedictorian or maybe not such a strong student, Dr. Coates basically shocks them into ‘OK, this is college,’” said Martin, adding that communication among the coaches, Bennett and the instructors is strong for a reason.

“We’re all in this together for these kids so they realize early that they can’t try something that it doesn’t get back to me,” Martin said.

If a student isn’t making at least a B-minus by midterm in Coates’ class, Coach Martin pulls them from practice until they turn things around during the final three weeks.

"If felt like we could do anything ..."

Jenna Weiner (Miami ’17) was one of 40 student-athletes with a 4.0 GPA during spring semester. Seven women soccer players earned 4.0s, the most of any Miami team. (Photo by Scott Kissell)

Nate Trawick, a junior defensive tackle from Richmond, Indiana, and a starter since freshman year, remembers how challenging Coates’ class was when he arrived on campus.

Trawick, an economics major with a marketing minor, finished this past academic year with a 3.18 GPA.

Looking back on that class, No. 96 said “getting there not knowing what to expect and then getting slammed with all that work, I first thought it was impossible, but after awhile you get used to it.”

Trawick appreciates Coates, whom he respects and views as a professor who wants them to succeed in all areas of life.

“By the time we got to fall, it felt like we could do anything with school and football,” he said. “It made balancing the two very easy.”

Coates enjoys running into the student-athletes on campus throughout their four years to catch up with them on how things are going.

He usually asks one question, “Did we get you ready?”

As with Trawick, the answer is always yes.

Trawick said he learned to prioritize his time, plan ahead and to stay on his game by keeping on top of his school work. He said the best part of the program was how much he improved in a small amount of time “and how much I matured.

“I felt like in a two-month period I grew in the classroom and as a person.”

Follow this writer on Twitter @margokissell.