Beyond the lava: Miami experts focus on volcanic hazards to people, ecology

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

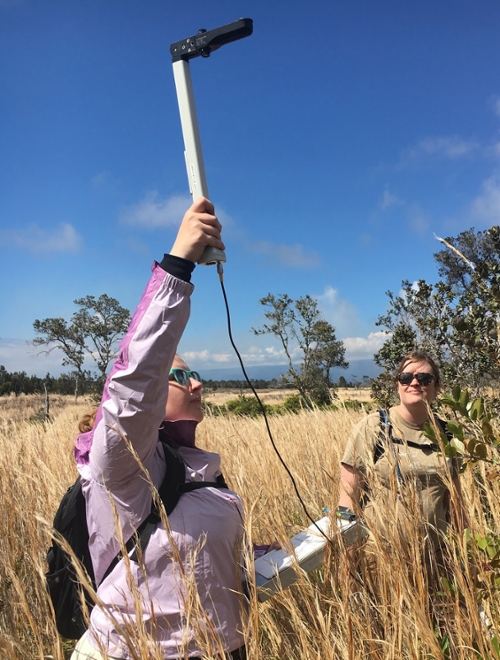

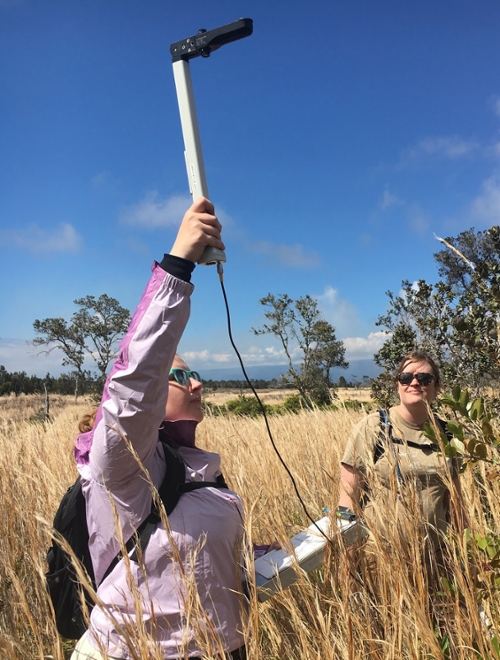

Jessica McCarty (left) takes leaf area index measurements on Kilauea in 2017.

As volcanoes in Hawaii and Guatemala simultaneously spew lava and belch toxic plumes of ash, experts at Miami University focus on the impact to humans and ecology in the surrounding area.

“There are a number of hazards in Hawaii right now that are above and beyond what most people think of when they see all these amazing pictures of the lava flows and lava fountaining,” said Elisabeth “Liz” Widom, the Janet & Elliot Baines Professor and chair of the department of geology and environmental earth science.

Widom just returned from a conference in Spain, where about 100 volcanologists discussed volcanic hazards while Hawaii’s Kilauea was grabbing headlines for lava bombs and unusual blue flames rising from the lava due to the presence of methane gas.

Her Miami colleague, Jessica McCarty, an assistant professor of geography, is part of a NASA project analyzing the effects of volcanic gas and thermal emissions from Kilauea on the surrounding landscape.

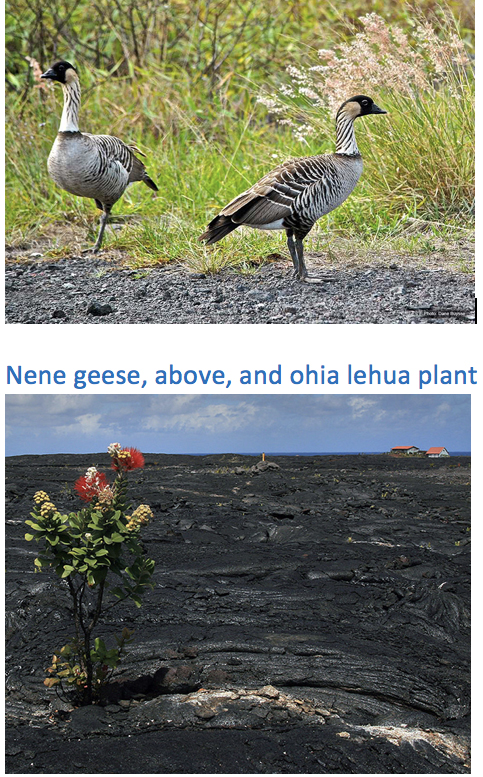

McCarty’s research focuses on vegetation, human communities, and impacts of landscape change on biodiversity, including the wild nene (Branta sandvicensis) geese, Hawaii’s official bird, which live on the lava fields.

Both Widom and McCarty have been to Kilauea.

Widom studied lavas from Kilauea for her senior thesis research in 1983-1984 and went there in 1991 as a gift to herself after earning her doctorate.

McCarty spent eight weeks there last year for NASA-funded research prior to joining Miami. She was part of a team collecting plant measurements for a large digital library documenting a spectrum of 173 plant samples on Kilauea.

In a symbolic gesture embracing the culture and ancient Hawaiian legend, Pele, the goddess of fire and volcanoes, McCarty made an offering of flowers, mangoes and a bottle of bourbon from her home state of Kentucky.

“Volcanoes are one place you will find geographers, geologists, atmospheric scientists — anyone who does natural science — because they are kind of our primordial laboratories,” she said.

Striking differences in lava, toxic ash

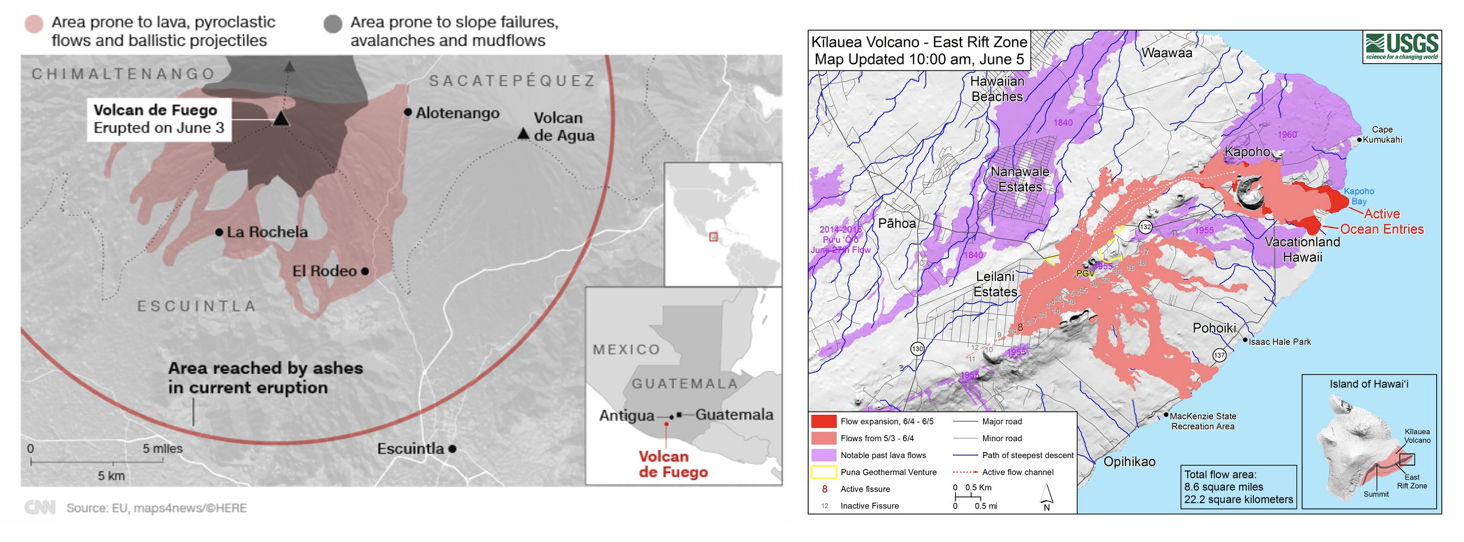

Differences between Hawaii’s Kilauea and Guatemala’s Fuego are striking.

While there have been no deaths from Kilauea four weeks after the May 3 eruption, Fuego already has claimed dozens of lives since it began erupting Sunday.

Fuego’s pyroclastic flows — hot clouds of gas and ash that are difficult to outrun — are why it’s been so deadly, said Kendall Hauer (Miami Ph.D. ’95), director of Miami’s Karl E. Limper Geology Museum located on the first floor of Shideler Hall.

Kilauea’s lava has a low viscosity “so it’s easily flowing lava with not that much gas in it,” he explained. “In Guatemala, it’s sort of the opposite. You have a very thick, sticky lava — or magma before it erupts – that is supercharged with gas.”

That causes the pressure to build within the magma chamber.

“It’s like taking a cap off a soda bottle you’ve shaken,” he said. “It just shoots out and it shatters the magma into billions of little pieces that then becomes the ash.”

While volcanic ash has been a problem in both places, Hawaii’s lava entering the ocean also has produced an additional threat: the creation of hydrochloric acid vapor that is corrosive and toxic to breathe, Widom noted.

Liz Widom (center) and colleagues at a volcano in Mexico.

Guatemala and Hawaii also have experienced the destruction of homes and other buildings. Three people had to be airlifted to safety in Hawaii after lava threatened and they became trapped in an isolated area.

Although reports have people in Guatemala heeding the warning, Widom said there has been growing concern about people in general not evacuating when they are told to leave.

“That’s a problem globally that volcanologists worry about — how to communicate with the public and how to deal with different cultures and try to understand what are the reasons they won’t leave, and how to communicate with them the hazards of staying,” she said.

Widom has taken graduate students as well as some undergraduate students to volcanoes around the world, including in Mexico and Madagascar, to conduct research.

Research focuses on ecological impact

This summer, McCarty hopes to work with a Miami undergraduate or graduate student to continue studying the impact on the ecology of Kilauea.

This summer, McCarty hopes to work with a Miami undergraduate or graduate student to continue studying the impact on the ecology of Kilauea.

The spectral library captured the state of vegetation pre-eruption, which will provide valuable information going forward.

“We will be able to type the vegetation that was destroyed by this eruption down to the species because we have the spectral response of individual species,” she said.

Scientists will be able to see what eventually takes root again.

The ohia lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), known for its fiery red flower, has adapted to its environment and been known to grow on the basalt rock.

Its aerial roots can replant atop hardened lava flows, she said. That comes after hundreds and thousands of years of adapting to living on an active volcano.

“Island biogeography is an amazing trip into watching evolution in progress,” said McCarty, who previously worked as a research engineer/scientist at Michigan Tech Research Institute.

Kilauea also is forming some kipukas where the lava doesn’t hit. These become preserved areas for plants and animals in the lava field, particularly used by the nene, an endangered species.

“Kipukas are essentially evolutionary petri dishes,” she said.

Curious and want to know more?

Curious and want to know more?

Follow McCarty on Twitter @jmccarty_geo.

Ask a Geologist: Kendall Hauer will gladly answer questions about anything having to do with geology. Email your questions to him at hauerkl@MiamiOH.edu.