Mineralogist John Rakovan: Solving the mysteries of the world's finest gold specimen with Los Alamos Neutron Science Center

Found in 1887, the Ram’s Horn is the finest known specimen of wire gold

By Susan Meikle, university news and communications

With the help of one of the world’s most powerful linear accelerators, a team of scientists have for the first time “looked” inside the finest known specimen of wire gold.

The Ram’s Horn gold specimen, found in 1887 at the Ground Hog Mine in Red Cliff, Colorado, is shaped like a twisted bunch of wires instead of the more recognizable golden nugget.

The 263 gram (about 9 ounces), 12 centimeter (4.7 inches) tall specimen belongs to the collection of the Mineralogical and Geological Museum at Harvard University (MGMH).

"Some native metals, a metal or metal alloy found in nature can occur in what is called wire morphology," said John Rakovan, professor of geology and environmental earth science at Miami University. "Much more common in silver, the wire morphology is rarely seen in gold samples, and this specimen is without question the finest known example."

"Almost nothing other than the existence of the specimen is known about wire gold," said Sven Vogel, a physicist at Los Alamos National Laboratory's neutron science center, LANSCE.

Academic collaborations: A win-win with Los Alamos National Laboratory

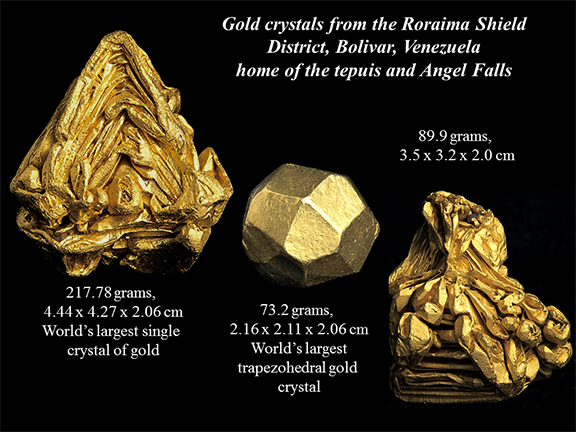

John Rakovan examines the world's largest single crystals of gold, from a 2014 study with LANSCE (photo by Scott Kissell).

The LANSCE accelerator — a half-mile-long particle accelerator that provides high- and low-energy protons and neutrons for a wide variety of scientific research — is mainly used for national security and fundamental science research. “We sometimes get to apply it to geological samples like this very famous gold specimen. It's a win-win for the Laboratory and the universities," Vogel said.

Using neutron diffractometry techniques, scientists can study the interiors of valuable specimens like this gold wire without having to cut into them or break them open.

No scientific studies have ever been published on the internal nature of this specimen, until now, according to Rakovan.

Read more about the study in World's finest gold specimen probed with Los Alamos neutrons, Feb. 13, 2019.

The research results suggest the wire gold is very different from wire silver. "Wire silver is a mosaic-like polycrystalline aggregate with many hundreds to thousands of crystals in a single wire," said Rakovan.

"The gold appears to be composed of only a few single crystals. Furthermore, we discovered that these samples are not pure gold, but rather gold-silver alloys with as much as 30 percent silver substituting for gold in the atomic structure."

The research team included Rakovan, Raquel Alonso-Perez, curator at MGMH, Frank Keutsch, professor of chemistry at Harvard University, and LANSCE scientists Vogel, Adrian Losko and Alex Long.

The wire gold study was done last summer in August and over winter term. The neutron irradiation made the sample radioactive and it had to "cool off” over the fall semester, Rakovan said.

Silver and gold

Calvin Anderson (right) accepting the Mandarino Award for Best Graduate Student Talk at the Rochester Mineralogical Symposium (2017).

Rakovan previously collaborated with scientists at LANSCE to study the world’s largest single crystals of gold. He is also an expert on wire silver formation. Because of this, he was approached by the Harvard scientists to collaborate on the wire gold research.

Rakovan and his doctoral student Calvin Anderson (Miami MS ’18) research the formation of wire silver. They recently discovered that the growth of wire silver leads to an unexpected isotope enrichment.

The Los Alamos team is using the neutron spectroscopy data to evaluate if isotope enrichment also occurs in these gold-silver alloys.

Anderson's research is supported by a grant from the Mineralogical Research Initiative (MRI). The goal of the MRI is to determine if there is a fair and reliable scientific method to identify whether wire silver specimens have formed naturally or have been artificially created.

World's largest single crystals of gold

The world's largest single crystals of gold, above at left and right, authenticated by Rakovan in 2014. He later determined the center "golf ball" specimen is not a single crystal (photo courtesy Los ALamos National Laboratory).

Rakovan was previously involved in another one-of-a-kind study with gold.

He was the first scientist to examine the world's largest single crystals of gold for authenticity. The structure and arrangement of gold crystals of that size had never been studied before, Rakovan said.

"There have been gold nuggets as big as several feet in diameter, but single crystals are usually quite small. It is rare for a single crystal of gold to be formed in nature the size of these world’s largest crystals,” Rakovan said.

That study also involved neutron characterization techniques and the use of the particle accelerator with Vogel and other colleagues at LANSCE.

“The question was whether Mother Nature is responsible for their beautifully faceted shapes. One alternative is that they were cast and made to appear as large single crystals," Rakovan said.

The largest single crystal of gold is about 1.75 inches wide (at left in photo) and was found to be natural. The "golf ball" specimen in the middle appears to have been cast, and is not a single crystal, Rakovan said this month.

Read more about that study in the Feb. 13, 2014 Miami news story: A golden opportunity: Miami geologist studies world's largest single crystals of gold.

Rakovan, who has a mineral named after him (Rakovanite), is also the executive editor of Rocks and Minerals.