Mack Hagood examines our fight to control noise with sound

Hagood coined the term 'orphic media.'

“Today’s sonic media technologies wield this orphic power but often neglect its communication potentials in order to control individual attention and personal comfort.

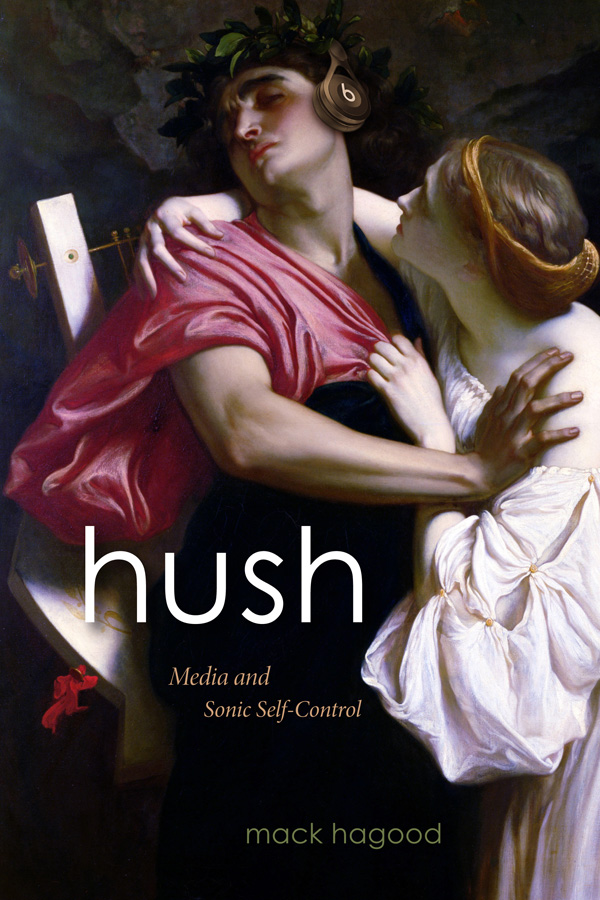

In the image, (which is the cover of the book), instead of singing and playing his lyre to connect with his love, Orpheus disconnects with noise-canceling headphones.” – Mack Hagood

Critics are making noise about "Hush"

Mack Hagood discovers that our feelings dictate our use of sound.

By Carole Johnson, university news and communications

The noise is positive for Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control, a new book by Miami University’s Mack Hagood.

The book’s focus is on how we use sound to change our environment. At its basic structure, sound can help us gain control, feel safe, create calm and perform productive work, according to Hagood, the Robert H. and Nancy J. Blayney Associate Professor of Comparative Media Studies.

Wanting to understand the role sound plays in how we connect or disconnect from today’s world, Hagood studied “orphic media” — a term he invented to describe apps, white noisemakers, noise-canceling headphones and other forms of technology used to create comfort.

“I wanted to highlight that the use of sound is not always conscious or intentional but more about how we are feeling,” he said.

His grandmother, for instance, slept with the television on after his grandfather died.

“It wasn’t informing her or even entertaining her. It was all about the light and the sound and people’s voices. She was all alone and it filled that space and made her feel safe,” he said.

Mack Hagood

Think of that all-so-wonderful sound of ocean waves breaking against a soft, sandy beach. For many, that can relieve stress. Enter in modern technology and one can have that sound anytime, anywhere.

Prior to our modern technologies,

Cue Muzak. While listening to comforting music helped workers be more productive, it was also used to entice shoppers to spend more money.

Personal listening devices gave us individual power

But with the inventions of personal listening devices, the power dynamic changed. Enter “the Walkman, a big moment in history where now an individual had control of sound,” he said. “A person can decide, ‘Do I want to communicate with others or lose myself in the music I choose?’”

And yet, at what cost is our control? Hagood observes that the same culture that invented these devices to provide peace, succumbs to capitalism’s siren call.

“Invention and consumerism make more noise, feeding into each other, and what was meant to control becomes out of control. There is never enough control,” he said.

For instance, the 24-hour a day cycle of constant emails, texts

"We need to turn something else on in order to turn ourselves off"

“It’s this feeling of something could be better. We rarely think of turning everything off; it’s often we need to turn something else on in order to turn ourselves off,” he said.

In an article that appeared in The Atlantic, Hagood writes about a new category of “in-ear products” called “hearables.” They selectively cancel out sounds you don’t want to hear.

“Those efforts seem less like plugging one’s ears to distraction and more like erasing whole categories of people and everyday experiences,” he wrote.

Regardless, media is a part of our environment, and its technologies allow us to adapt. He’s curious as to how people with disabilities can use sound technologies to help them feel better.

One chapter in his book discusses tinnitus, a condition in which people hear a constant ring. The New Yorker describes this chapter as moving based on Hagood’s personal experiences.

“He writes movingly about ‘listening to tinnitus and hearing it as a loss of silence, a loss of choice, and finally, as a loss of self.’”

Hagood is continuing his work in disabilities studies and what role orphic media has for people.

Hush is available at Duke University Presses, Google Books, IndieBound