Latest award spotlights unique relationship between the two Miamis

Neepwaantiinki: “learning from each other”

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

Haley Shea (Miami ’13) became involved in the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma’s Summer Youth Educational Experience as a young girl growing up in Indiana. She learned more about her tribe’s culture and language during the camps and began forging her own identity.

That education into her Native American heritage continued at Miami University, where she double majored in psychology and Spanish and took additional classes through the Myaamia Heritage Award Program.

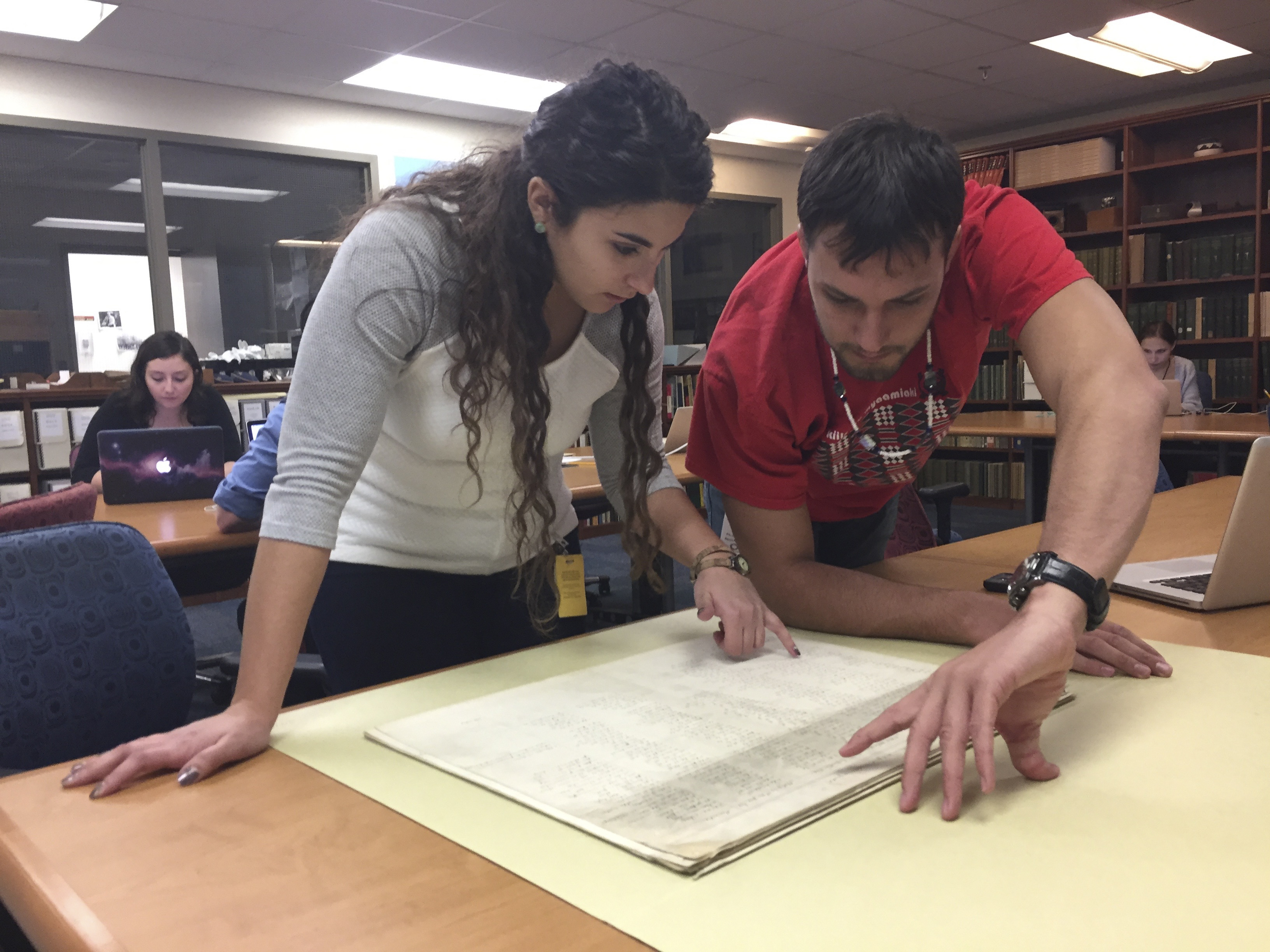

Daryl Baldwin and Haley Shea review documents at the Myaamia Center (photo by Karen Baldwin).

The program, which began in 1991, is a four-year undergraduate college experience for Miami tribe students enrolled at the Oxford campus. It provides a tuition waiver and the additional coursework relative to their heritage.

Shea — who earned a doctorate in counseling psychology last year — is back on Miami’s Oxford campus working halftime as a research associate at the Myaamia Center, a research-focused collaboration between the tribe and university. The rest of her time is spent as a visiting assistant professor of educational psychology.

Returning to Miami was always her goal.

“The tribe has given me so much throughout my life, both in terms of my own identity formation as well as financial, educational support — all of these different types of support,” she said.

“I feel a sense of responsibility to give back to my community.”

A tribal nation trying to rebuild itself

At the Myaamia Center, Shea has joined her sister, Kara Strass (Miami MS ’18), who was recently promoted from Miami Tribe Relations assistant to director of the Miami Tribe Relations office after Bobbe Burke retired.

Strass and Shea are examples of what Myaamia Center director Daryl Baldwin hoped the center could be — “a space to help us as a tribal community develop our young intellectuals into individuals who could contribute back to our tribal nation that is trying to rebuild itself.”

Kara Strass and Jarrid Baldwin examine a Myaamia language document at the Smithsonian's Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. (photo by Gabriela Pérez Báez)

The Myaamia Center has been leading a language and cultural revitalization effort that has resulted in the first generation in nearly 100 years learning to speak the Myaamia language.

Baldwin credits the unique relationship between the two Miamis — the sovereign tribal nation and the public educational institution — with playing a key role. At Miami, tribe students have the unique experience of learning together and expanding their knowledge about their own heritage and culture.

The Myaamia word neepwaantiinki, which means “learning from each other,” embodies the core understanding of this relationship. It captures the desire to mutually engage with each other by creating opportunities for learning and sharing.

The statistics are impressive:

- To date, 85 Myaamia students have graduated from Miami, including 80 with undergraduate degrees and eight with graduate degrees. Three people have earned both.

- The 6-year graduation rate for Miami tribe students is 89.4 percent, compared to the national average of 41 percent for Native Americans in 2017.

- Thirty-two Miami tribe students are enrolled at Miami this academic year.

Tribe and Myaamia Center recognized

For its efforts, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma has earned national recognition, including a 2018 Honoring Nations Award from the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development.

More recently, the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas earlier this month awarded Baldwin and the Myaamia Center staff with the 2019 Ken Hale Prize. The award honors “outstanding community language work and a deep commitment to the documentation, maintenance, promotion and revitalization of indigenous languages in the Americas.”

The Myaamia Heritage Logo references the traditional Miami tribe art form of ribbonwork and symbolizes the relationship between the university and tribe.

Baldwin said the prize recognizes “the collaborative work we all do through the Myaamia Center because of this unique relationship we have with a tribe and university.” The center has 20 full- or part-time staff, including faculty affiliates who Baldwin said provide important institutional support.

The center has worked to revitalize endangered languages through the National Breath of Life Archival Institute for Indigenous Languages workshops.

Gabriela Pérez Báez, assistant professor of linguistics at the University of Oregon and co-director of National Breath of Life with Baldwin, said the relationship between the two Miamis is unique.

"Language revitalization is a worldwide movement. Practitioners in a diversity of contexts recognize the need to forge partnerships to support revitalization efforts. These partnerships are at various stages depending on a variety of factors," she said. "The partnership between the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and Miami University is nearly 50 years strong and thus lets the global community of revitalizationists visualize the power of collaboration."

A unique perspective on revitalization effort

Strass said she always felt connected to her Native American ancestry because of her grandmother, who often shared stories about her experiences growing up. But it wasn’t until she came to Miami that she discovered other aspects of her identity.

As she pursued a master’s degree in student affairs in higher education, Strass began learning the Myaamia language and more about her Miami tribe’s history and culture.

“The language, culture and games, and extending that kinship network, all of those have been really important to me coming to a deeper understanding of who I am,” she said.

Kara Strass, left, and her sister, Haley Shea, sitting, play the moccasin game at January's Winter Gathering in Miami, Oklahoma (photo by Karen Baldwin).

Shea is a member of the Myaamia Center’s Nipwaayoni Acquisition and Assessment Team, which studies the impact of the tribe’s ongoing language and cultural revitalization initiatives on citizens of the tribe, especially the children.

“Haley came up through our youth programs beginning at the age of 10, so she brings a very unique perspective to the revitalization experience and its impacts on youth,” Baldwin said.

Today, about 80 youth, ages 6 to 16, participate annually in the Saakaciweeta and Eewansaapita Summer Youth Educational Experiences in Oklahoma and Indiana.

Shea examines factors that have contributed to the positive outcomes for tribe students.

“I think a large part of why our students are succeeding is because of that connection, belongingness and creating a community.”

An open house at Bonham House, where the Myaamia Center is located, is from 1-4 p.m. Feb. 7. Enjoy refreshments, visit with staff and explore the Myaamia space.

A “Myaamia Ribbonwork” exhibition opened this week at the Miami University Art Museum. It runs through June 13.