The story of Miami and the Miami Tribe is one of passion for education and revitalization

Myaamia Center weaves the past and present into a promising future

Editor’s Note: It’s been 24 years now since Miami University became the Miami RedHawks, but it’s been almost 50 years since the beginning of a new relationship between the university and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. During the years, significant milestones were achieved that go beyond the change of a mascot name but were accomplished in part because of it. The change led the way to a deep understanding within the relationship that generated a steadfast determination to strive for educational excellence.

Kara Strass is at the epicenter of this transformation as the director of Miami Tribe Relations and as a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. She works at the Myaamia Center, the research arm of the Miami Tribe, housed on the campus of Miami University. The center is leading a language and cultural revitalization effort. Just recently, its newest project with the Ohio History Connection launched. This education project will bring the Myaamia culture and imagery to thousands of fourth graders as part of the K-12 Ohio as America curriculum.

Daryl Baldwin, director of the center, credits the relationship between the two Miamis — the sovereign tribal nation and the public educational institution — for these and many other milestones, including scholarships to Miami Tribe students.

Miami President Greg Crawford said, “We are truly honored to have the Myaamia Center as part of our campus community, and we are grateful to have a strong relationship with the Miami Tribe. We believe the Myaamia Center is a model for the nation.”

Miami University President Gregory Crawford and Miami Tribe of Oklahoma Chief Douglas Lankford sign the 2017 Memorandum of Agreement creating the Myaamia Heritage Logo, a jointly owned logo between the Tribe and University that represents the relationship between the two partners.

The story of those almost 50 years is powerful and serves as inspiration in this time in our country as the nation reflects on what it means to respect each other, to honor our differences and to learn through various perspectives.

Strass recounts the history of this relationship, and as with most relationships, it’s complicated, filled with intense emotions and misunderstandings. The historical chapters of this story, however, culminate with an epilogue that describes a remarkable present and a promising future.

The following is a historical account written by Kara Strass.

History

Miami University’s name reflects the history of the Native American tribe that once lived in the lower great lakes, including the Miami Valley region of Ohio. Miami University was named for the Miami River valley, which was named for the Myaamia (Miami) people. The fact that Miami University carries the name of a Tribal Nation, and is located within the historic homelands of the Myaamia people, lays the foundation for this special relationship, which started almost 50 years ago.

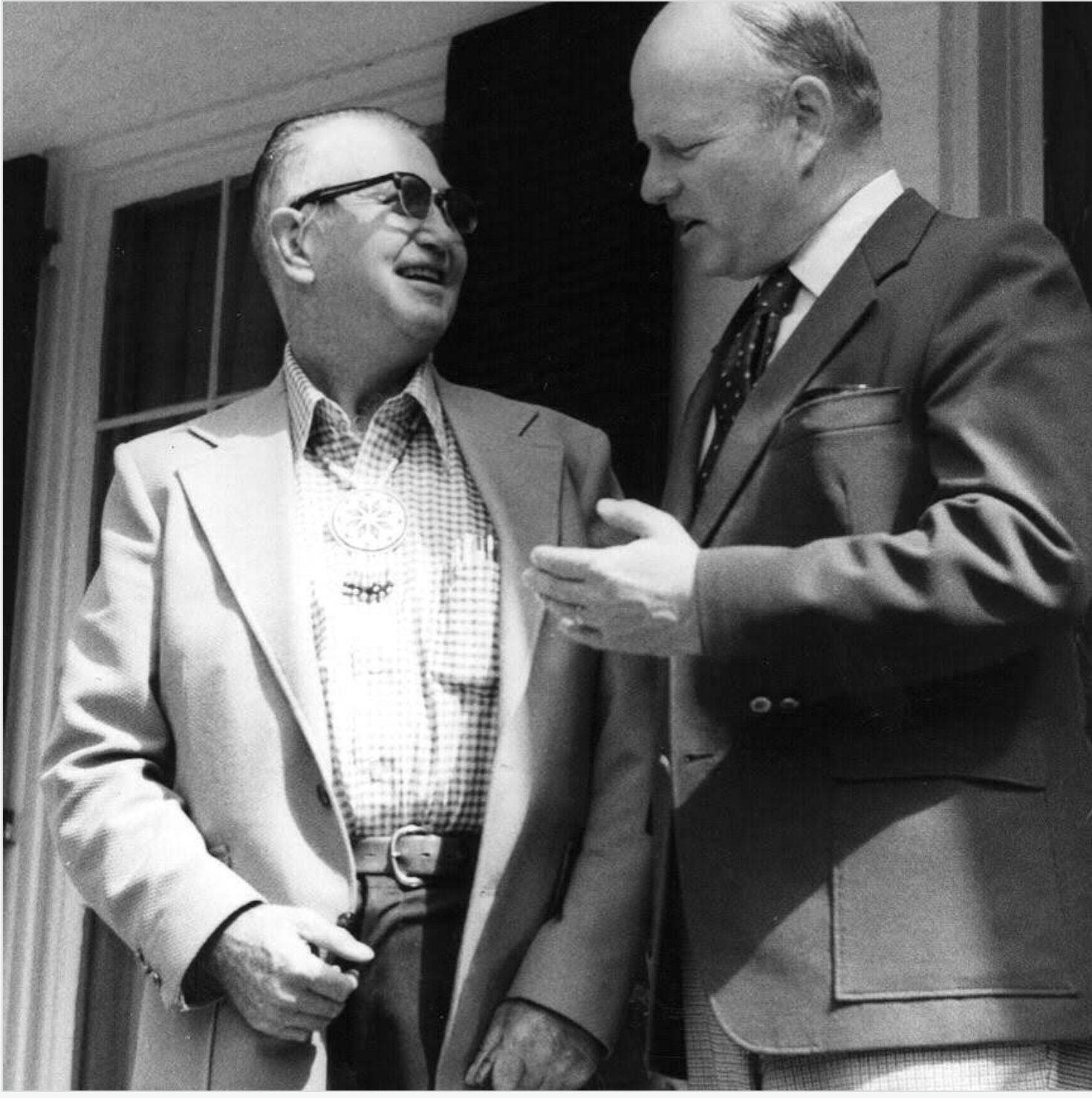

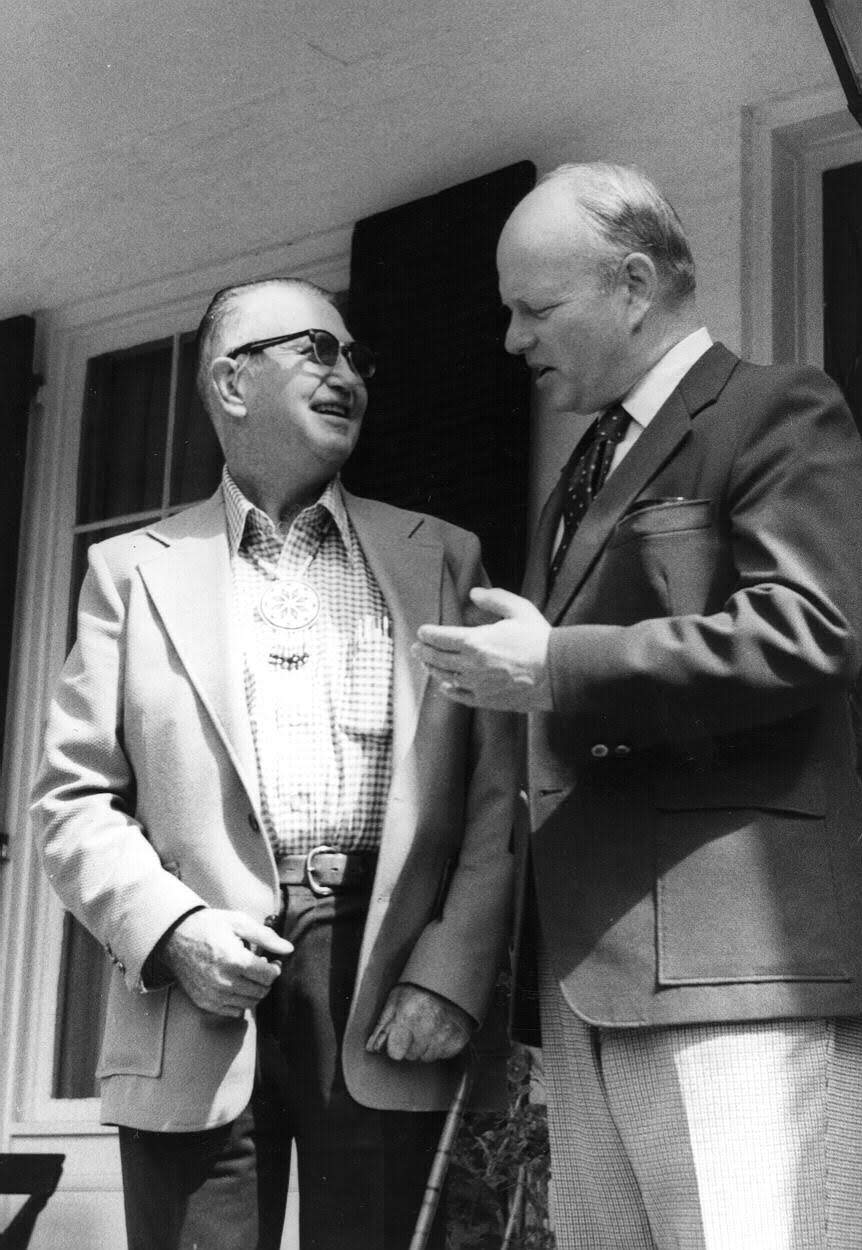

Miami Tribe of Oklahoma Chief, Forest Olds, with Miami University President, Phillip Shriver, when Chief Olds visited Miami University in 1974.

In 1972, then chief of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Forest Olds, visited Miami University unexpectedly. While this visit set the groundwork for what would become a rich and meaningful relationship, it also played a role in the battle of the mascot name that culminated in 1996 when Miami became the RedHawks.

Today’s confusion by many lies in competing historical facts — a 1972 resolution and what led to the 1996 resolution. Following Old’s visit to Miami in 1972, the university asked the Tribe to officially sanction the use of its mascot. A resolution was written by Miami University and sent to the Tribe to consider. After much discussion, the resolution was passed by the Tribe’s general membership at their 1972 Annual Meeting. This resolution was long used by Miami as a reason that they would continue to use a race-based mascot and is still used by some alumni today who argue that the change was not necessary.

The relationship between the Tribe and the university continued to grow, but much of the focus remained around Miami’s mascot. New imagery was created in consultation with the Tribe that was meant to be more authentic and representative of Miami people. A student mascot was created to dance at athletic events, and the student received regalia and "fancy-dance" training from the Tribe. There was much effort by both Miami University and the Miami Tribe to create educational opportunities for the campus community and to provide authenticity and accuracy to the mascot. Even as this work was being done, the mascot continued to wear the regalia of a fancy-dancer, danced to a large drum and even rode into the football stadium on horseback. None of these actions are based in Myaamia culture. As hard as everyone involved tried, we can now see that the presence and promotion of a race-based mascot hindered the ability of Miami University to create a climate of understanding and respect toward members of the Tribal community.

Starting in the 90s, Miami developed recommendations for strengthening the university’s relationship with the Miami Tribe and organized a public forum to discuss the mascot controversy in 1993. However, Miami continued to use the mascot until the general membership of the Miami Tribe in July 1996 passed a resolution asking Miami to change the name.

WHEREAS: We realize that society changes, and that what was intended to be a tribute to both Miami University, and to the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, is no longer perceived as positive by some members of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami University, and society at large; and

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma can no longer support the use of the nickname Redskins and suggest that the Board of Trustees of Miami University discontinue the use of Redskins or other Indian related names, in connection with its athletic teams, effective with the end of the 1996-97 academic school year.

Miami University’s Board of Trustees passed a resolution in September 1996 recommending the change of Miami’s mascot. A committee was established to find a new mascot, and in the 1997-98 academic year, Miami became the RedHawks. Miami University’s quick action after the Miami Tribe made the request was a recognition of the sovereignty of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and shows that the university had a deep respect for the relationship that had been established. Native American advocacy groups, including the National Congress of the American Indian and the American Indian Educational Association, have been calling for an end to race-based mascots for years, while change has been slower at the national level. The fact that Miami University changed the mascot so quickly after input from the Tribe shows that the administration acknowledged that the Miami Tribe is a living community able to change its mind and that the Tribe’s decisions should be respected.

Julie Olds, cultural resource officer for the Miami Tribe, said, “In relationships, sometimes change can be a difficult passage, but when the need to seek change is born of respectful, informed consideration and is presented and met with the same, that passage can lead through the difficult to greater, more meaningful opportunities.”

The road to excellence - neepwaantiinki or "learning from each other"

Even during the early 1990s when the controversy over Miami’s mascot was intensifying, Miami continued to strengthen the relationship with the Miami Tribe, primarily through education.

The Myaamia Heritage Award, which offers Miami Tribe students support to attend Miami University, was established in 1991. The first year of the program, three students enrolled at Miami, and 13 students had enrolled by 1997 by the time the mascot was changed. Since the mascot change, the number of Myaamia students at Miami University has only continued to grow, and today there are 95 graduates of the Myaamia Heritage Program, and we will have more than 30 Tribe students on campus in the 2020-21 academic year. These students choose to come to Miami from across the country to advance their knowledge and understanding about their language and culture.

Myaamia students represent the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma in President Crawford’s 2016 inauguration parade.

Program assessment shows that these students leave with a better understanding of who they are as Myaamia people and a deeper commitment towards the preservation of their cultural heritage.

The relationship between Miami University and the Miami Tribe has evolved into a multilayered collaboration built on trust, respect and a shared commitment to education, which is expressed in the Myaamia language as neepwaantiinki or "learning from each other."

Major outcomes of this relationship include the development of the Myaamia Center, the Myaamia Heritage Program and the ever-expanding research that is done in collaboration with Miami University faculty and students.

It is because of the strengthened relationship after the mascot name change that the Tribe was able to approach the university about the creation of the Myaamia Project (now the Myaamia Center) in 2001.

The Myaamia Center

Starting out with a single employee, the Myaamia Project was focused on revitalizing the Myaamia language. In 2008, the university and the Tribe signed a Memorandum of Agreement that outlined the work of the Myaamia Project. Once again, Miami University acknowledged and respected the sovereignty of the Miami Tribe by agreeing that all cultural and intellectual property created by the Myaamia Project be under the proprietary control of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. The Myaamia Project continued to grow and develop until it became the Myaamia Center in 2013, which allowed for additional capacity building and growth. Today, the Myaamia Center has six full-time and 10 part-time staff. It focuses on language and cultural education development, and its work directly serves the needs of the Miami Tribe with a strong commitment to share the work on campus with faculty, staff and students.

Daryl Baldwin, Myaamia Center Director, reflects on the creation of the center and the impact of the mascot change.

“When I came to campus in 2001 to serve as the founding director of what was then called the Myaamia Project for Language Revitalization, there were no other university-tribe models for me to look at. So I understood we were building something new. I was also keenly aware of the recent mascot change to RedHawks, and it was important to me personally that our language revitalization work on campus was not carried out in the shadow of a racial mascot. The termination of the mascot cleared the way for new educational experiences that would become important to the development of the Myaamia Center today.”

It is because of our history of two forced removals, boarding schools and other forced assimilation practices that the Myaamia language and culture began to decline. By the middle of the 20th century, there were no longer any speakers of Myaamiataweenki, the Miami language. Reclaiming and revitalizing our language from documentation has required extensive research with thousands of pages from archival documents, some of which date to the 1690s. We are able to teach and use the Myaamia language again today because of the work that has been done at the Myaamia Center with the help of our partners at Miami University. The university provides a climate of sharing and engagement for this work that includes a wide range of resources, tools and academic partners that allow us to significantly advance this effort.

If you were to come into Bonham House today (not during COVID-19, but in regular times), what you would find is a lively, vibrant community of Myaamia people and allies who are working tirelessly to recover our language and culture and to share that information with Miami University. The walls are covered in Myaamia imagery, and you are likely to hear the echoes of Myaamiaataweenki used throughout the building. Miami University aids in this work in numerous ways — through financial support as well as through our partnerships with faculty and staff. The history of the Miami Tribe is now intertwined with Miami University, and that partnership has helped our community to grow and flourish, but this is only possible because Miami University took the right step years ago to focus on education and relationship building with the Miami Tribe. Something a mascot could never achieve.

tapaalintioni nahiteehioni ‘Love and Honor’ – Kara Strass